When Dan introduced me to Chew it was the odd premise that convinced me to give it a shot. The entertaining introductions to the powers and the prologues that have the reader wondering how it’s going to tie into the issue’s content intrigued me. (As did Guillory’s unique art style) But the biggest point in Chew’s favor was the fact that it had a finite end. Writer John Layman knew it was a 60 issue story and, as he reveals in the third Smorgasbord collection, he knew the ending he wanted right at the beginning. The fact that it would end raised the stakes because it meant no one was safe, no one had to be saved for generations to come. And, as I would discover, the fixed ending allowed Layman to engage in the kind of tight plotting that often eludes the never-ending comics. I’d like to explore this a bit further before delving into Chew’s themes.

It’s axiomatic at this point that death is cheap in comics. When I first got into comics, death was so impermanent that we had the saying “the only permanent deaths are Gwen Stacey, Bucky Barnes, and Uncle Ben.” I’m not up to date on the latest spider-machinations of Dan Slott, but I believe Uncle Ben remains the only one on that list because his death is THE inciting incident that creates Spider-Man the hero (as opposed to Spider-Man the wrestler). I believe at this point the only reason death issues continue to sell is not because readers believe in them anymore, but because they want to see what in-universe loopholes have been used to kill our gods. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that at some point in the last decade I read an issue where Wolverine was burnt to a crisp and his healing factor was able to bring him back. So his death a few years ago had to really involve something special.

We can’t blame Disney or Warner Brothers for this, however. Although there was a time before the Avengers or the X-Men or Superman, we seem to be stuck with these properties. Their proteges are forever stuck as second banana unless the heroes are spending some time dead, as in the case of the storyline in the early 2000s where Dick Grayson was finally able to step up after 40 years thanks to Batman’s death. So the deaths cannot stick because there are new generations of kids who need to have their Bruce Wayne, Scott Summers, etc stories. So we never get satisfying endings, the villains never stay in Arkham, etc. It can be a little tiresome after a while. It also means that you’re always playing with the neighborhood toys. If someone else gets a hold of a character they can undo everything you’ve done. It’s why we have retcons. It’s why things get messy with character histories. It’s why you can’t do tight plotting for more than a story arc’s worth of stories.

Layman is able to hit us a lot harder because these characters are DONE. He knew that was coming and so deaths hurt, especially after Layman has spent so much time building up these characters into real people. Real people in a world with sometimes silly and sometimes deadly serious powers. While there are plenty of indie comics with unending stories, it’s this ability to put a cap on things that has drawn me closer to these and away from mainstream comics.

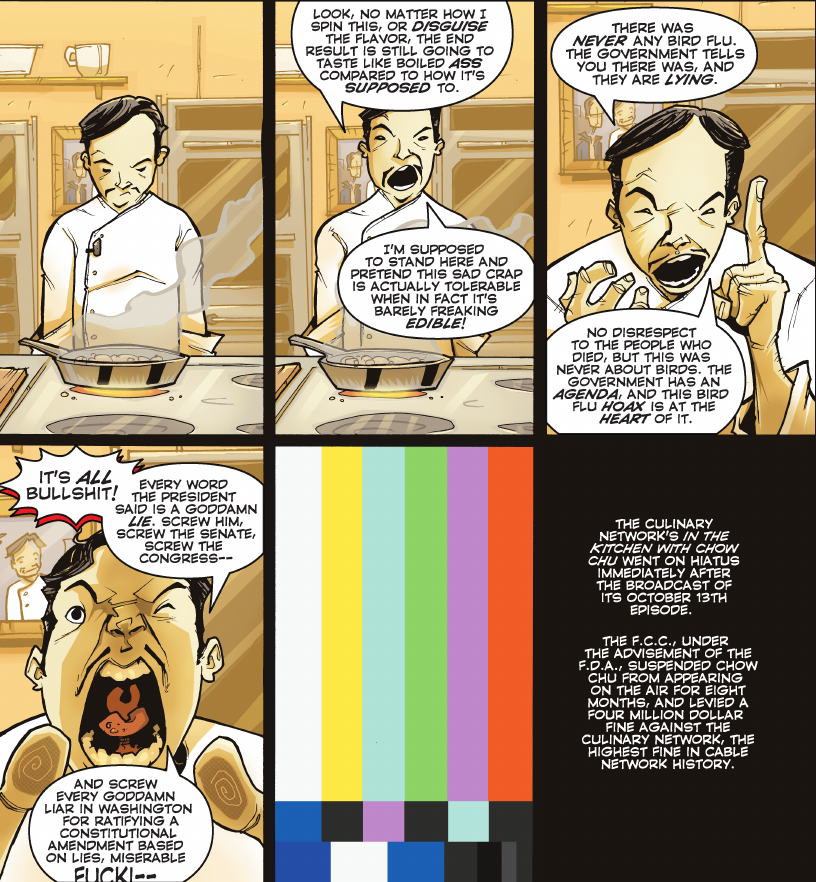

Because I knew I would be writing an article encompassing the entire sixty-issue run, I went back to the beginning and read all the way through to the end. I’d already read up to Major League Chew, so I had some idea of where things were headed when I picked volume one back up for this re-read in preparation. This time I realized just how tightly Layman had plotted this series. In the first volume, in a torrent of world-building, we see all of the following even if we don’t know the significance for many volumes to come: frogs all over Montero’s office and the fact that Caesar is working for him, the planet with the words over the skies, the “vampire” cibopath, and the possibility that the bird flu was a conspiracy. That last one in particular is a great bit of narrative because we are quite familiar with people who see conspiracies everywhere and would of course just dismiss this as simple world-building. Of course, our first hint that it might be more important is when Savoy, who was introduced as a mentor and source of reason, seems to hint that it might indeed have been a conspiracy.

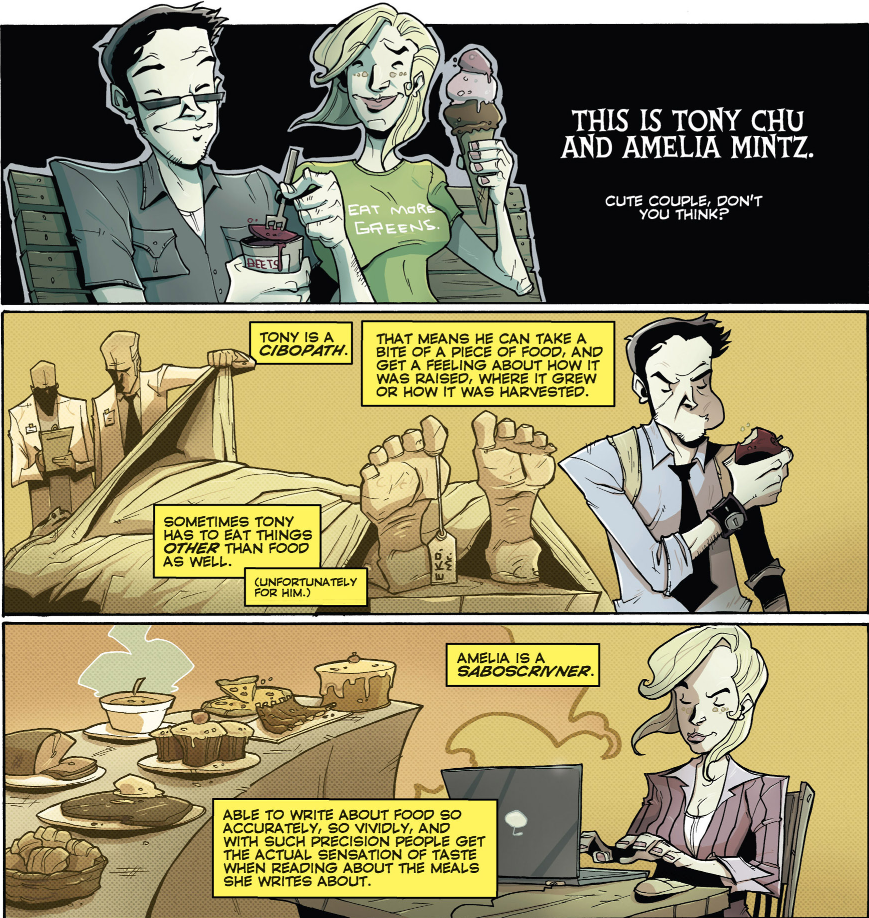

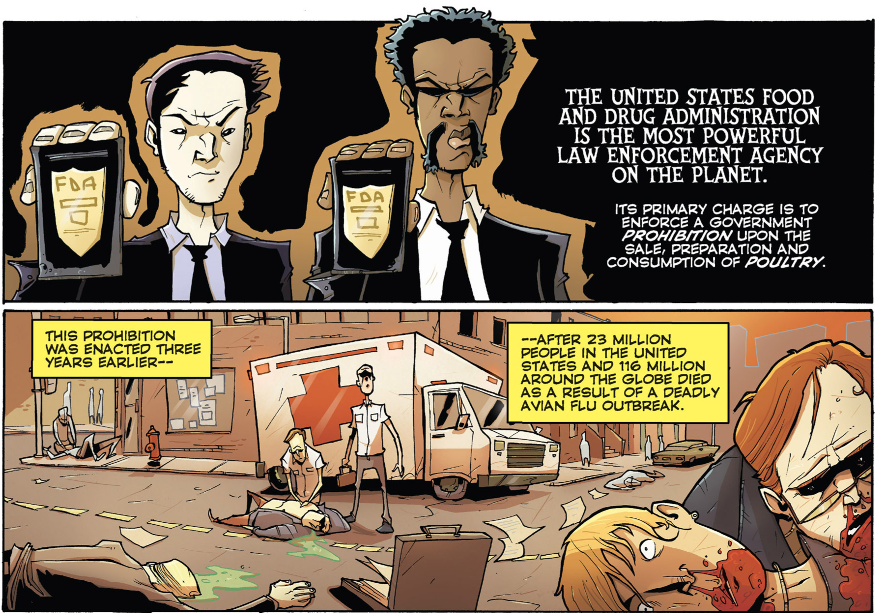

A very quick synopsis if you are reading this and don’t know what Chew is about: after a deadly bird flu outbreak chicken is outlawed in the United States. The FDA gains an FBI-like police force to combat food and chicken crimes. Just as when we had alcohol prohibition in the 1920s, there are chicken speakeasies where one can eat chicken illegally. Outside of that, the big difference from the real world is that a segment of the population has food-related powers. These powers are all over the place and contribute the humor to what is otherwise a relatively dramatic story. For example, having the power for people to taste any food you write about or learning about the food you eat or being able to craft working weapons from food. Tony Chu, our protagonist works for the FDA police force.

Chew #1 has a publish date of 3 June 2009 and Layman writes at the end of the third Smorgasbord edition that he came to Guillory with the idea in 2008. From 2005-2007 bird flu was making more and more headlines, with an epidemic hitting early 2009. Additionally, the George W. Bush administration was nearing its end as Layman gestated the ideas for Chew. The terror attacks of 2001 had led to a ballooning of government agencies that included beefing up Homeland Security. It went from a relatively obscure agency to absorbing the Secret Service from Treasury where the Secret Service had been situated for about 100 years. Newspapers began (and continue) to report of border agents acting with impunity. And, of course, the 11 September attacks are rivaled only by the Kennedy assassination for conspiracy theories. All of these melded together to form the main themes gluing together a police procedural taking place in a wacky offshoot of our universe. Layman also spoke to what such a government infrastructure might do to the morality of its employees.

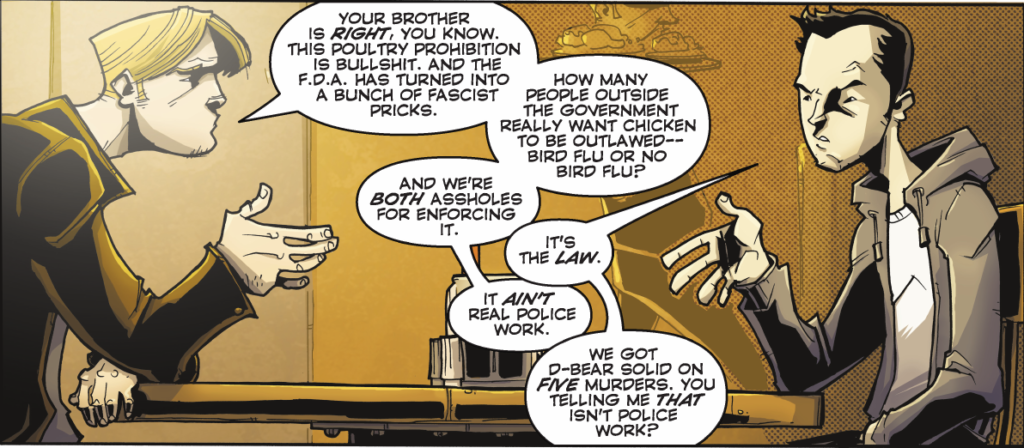

The trope of the incorruptible cop paired with one that’s a little loose with morality is nothing new. It’s often been used to cause dramatic tension between officers as well as commenting on the relative merits of each approach. In Chew we have Tony Chu on one side and Savoy/Colby on the other side, each representing a different take on the rule-breaker lawman. It doesn’t matter how much suffering Tony Chu goes through or how much abuse he gets from his boss, Tony Chu is always going to do each mission by the book. He believes in the justice system and doing what’s right. He’s the cop we all say we want until we’re affected and then we want a Batman vigilante instead. John Colby is a Han Solo with a badge type. While his actions are sometimes satisfying to watch and even sometimes a bit more effective in getting information during a case, he abuses his role – especially as he graduates to the FDA and USDA. He flagrantly eats chicken the entire run, even as it becomes his job to enforce the government rules against it. He’s a fun character to watch, but he’s not really want we want in a police officer. Then there’s Maison Savoy. He breaks rules, but not to enrich himself. His wife died during the bird flu epidemic that led to the chicken prohibition so he’s highly interested in figuring out whether there was a conspiracy or if it was just like the Spanish Flu. He’s the rule-breaker for a higher purpose. It’s obvious why Chu would shy away from Colby’s antics, but the reader could certainly be sympathetic with Chew getting on the slippery slope thanks to Savoy. The fact that he doesn’t is a source of tension between them and fuels many aspects of the story past the first volume. In fact, it propels the final story arc that concludes the story. Not only does Chu’s unwavering dedication to following the rules ground the story as everyone around him bends the rules, it also makes the final panel have a really strong impact.

While the bulk of the story involves the effects of the government expansion (FDA and USDA getting FBI/SWAT-like forces), it turns out that the bird flu was indeed a government conspiracy. It was the case of the government fabricating an event in order to gain consensus. There are a few of these throughout history, the inciting ship explosion for the Vietnam War being among them. Rather than explain to the American people that they had decoded a message from the aliens that chicken was doom, they created the death to force the attitude change they wanted. (Interestingly, not too far from the planned calamity in Watchmen). So an overarching theme of the series (both on the surface in the case of the FDA and USDA and as a thread unknown until the end with the conspiracy) is that of the paternalistic state. The government knows what’s right for the citizens and the end always justifies the means. I can’t think of a better way to explore these ideas in the mainstream than through a comic that has the issues woven throughout the background. It keeps the story from being an anvilicious Aesop and allows the ideas to entered unfiltered through the biases of our usual political debates.

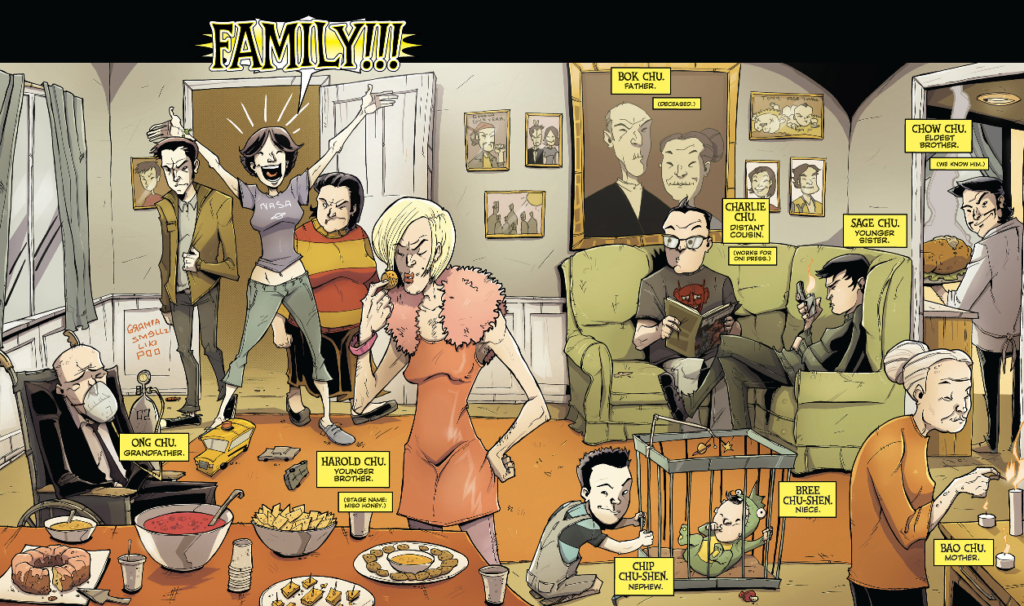

There are other great aspects to Chew, including the fact that the protagonist is Asian. There is a distinct lack of Asians in American mainstream comics. Oh, there are a few second-string characters like Karma (Xi’an Coy Manh) of the X-Men, but for the Asian-American comic book fan there aren’t many heroes to see oneself in. And of those, there even fewer who aren’t martial arts masters. In fact, continuing on Layman’s eschewing of Asian stereotypes, there’s the Chu family. One gets the distinct impression that the Chu family has been in America for at least a couple generations, so the family is mostly no-different that the average American family. You can hear about Layman’s reasons for creating an Asian-American protagonist in the interview I conducted with him at the 2016 Baltimore Comic-Con.

I also want to mention that a key part of why Chew works so well is Rob Guillory’s art. It is a caricatured version of the world that retains enough realism to hit the dramatic notes while also being silly enough to make the fantastical elements not feel incongruent. Additionally, Rob’s easter eggs throughout the series serve to both give the world a more lived-in feel (the message boards have actual messages on them! The memos aren’t just scribbled lines!) and give fans something to look for and chuckle about. You can hear about about that in my interview with Rob Guillory from Baltimore Comic-Con 2016.

I don’t know if we’re ever going to return to the days where the major publishers put out comics of every genre – love, crime, teen, western, science fiction, and, yes, Super Heroes. But Layman and Guillory have shown that there is a market out there for something different – for detective procedurals, for Buffy-style storytelling with a bad guy of the trade as well as an over-arcing story, for non-white characters, and for stories that have definite endings. I can’t wait to see what he does next in the indie world.

Long time readers of Comic POW! will also remember back when Dan and I were the main writers, we used to challenge each other to choose an issue from our pull lists to convince the other person was the better issue. You can see those in Week 11: Batman #5 vs Chew #23 and Week 18: Chew #31 vs Saga Chapter Nine.

Great series! I’m glad you really liked it

[…] LOVED Chew here and I’ve been waiting and waiting for Rob or John to announce a new project. Well, […]