I am a huge fan of Matt Fraction. His run on Hawkeye is one of the best Marvel comic runs of the decade; Sex Criminals is so innovative, emotional, and honest; The Defenders was a trippy run; Satellite Sam great for early television nerds. So I excitedly went into ODY-C which was not only sold as a gender-flipped Odyssey, but also takes place in outer space.

Before I get into the themes of this collection of the first twelve issues, I wanted to deal with my one criticism of this project. Like many educated folks in the west, I have a grasp of the plot summary of the Odyssey, but have never read a translation. Fraction chooses to hew close to the source material’s words while adapting the visuals – similar to Baz Luhrman’s Romeo + Juliet. Coupled with Christian Ward’s abstract art style, it can be very hard to understand what is going on at times. The art is amazing and evocative and the layouts often contribute strongly to evoking feelings that really elevate the book to an art form rather than simply a colorful set of panels in a row.

With that out of the way, I’d like to explore the major theme of this adaptation – gender. (Of course, there are themes like leadership, the hero’s journey, the will of the gods, etc – but those are present in the original source material) What’s interesting, and it’s addressed in one of the essays at the end, is that the book is not a pure gender swap. Yes, many of the characters have been swapped, but some characters remain the same gender and this has a much larger effect than a mere gender swap. Within the narrative, the impetus for this is a prophecy (of course) that a man will be Zeus’s undoing. So all men are eliminated from the universe. In order for the human race to continue the Sebex are created to fertilize eggs and produce more women or Sebex. However, sometimes the gods mess with things and there is a male birth.

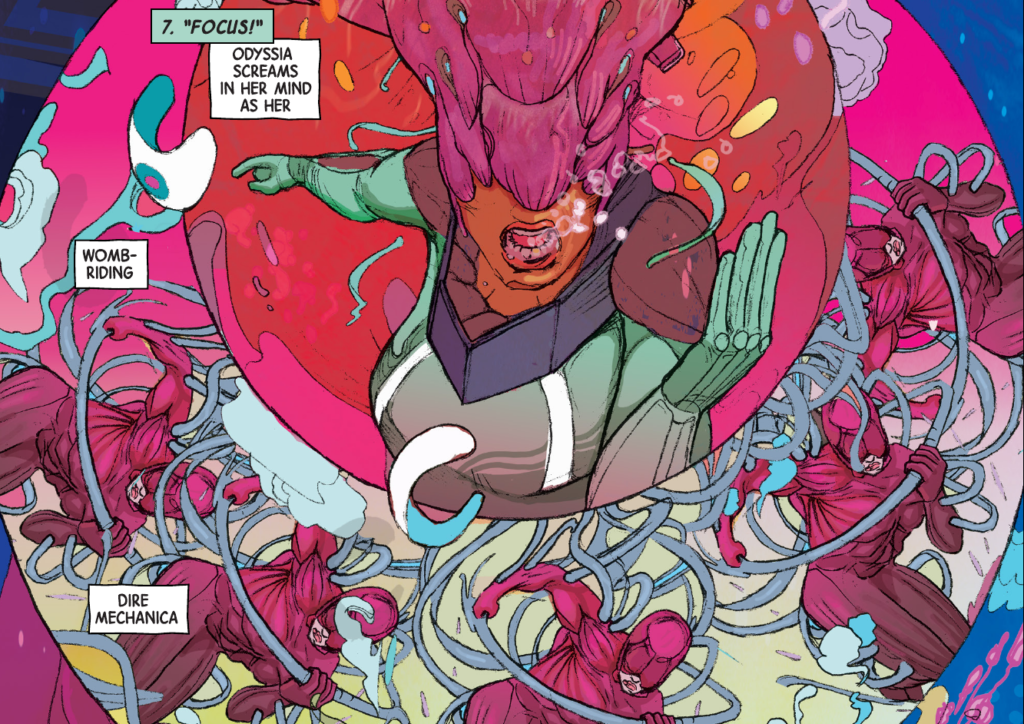

In some cases, the effect of the gender swap is to contrast male and female roles both in the original Greek sources and as modern readers with modern notions of gender roles. With Odyssia, for example, there is the constant contrast of her display of what we would consider masculinity with the fact that she’s a woman and a mother. Many times she seems to not be maternal and chastises her Sebex for wishing to have another child. It often seems she is in more of a hurry to reunite with her wife than to see a child that has grown in her absence. However, as one of the essays at the back of the book makes clear, there are some actions that Odyssia takes in comparison with her original male counterpart. In the original Greek society that the Odyssey comes from, Odysseus was displaying female traits whenever he was crafty with his foes. So by switching him to a woman, this is less of a shock. Although, all these centuries later, while there is still the trope of a woman using her “feminine wiles”, it’s much more of a gender neutral trait.

The second of the book deals with He, the counterpart to the original’s Helen. Once again, it was lust and marriage over an individual that leads to the war of Troy. This time is is a man who is mainly wanted for his looks. In fact, he draws his entire worth from being coveted by the women around him. They went to war over him! And so he is set adrift and without a purpose after he is freed from his “slavery” by the brother-kinds from Q’af who declare men should not be treated this way. I am not a woman, but first and second-hand that is much more often a set of emotions women have to deal with in modern western society. It is at least partially responsible for the trend in youth-restoration plastic surgery. We tell women (especially those in visual careers) that their worth is in their sex appeal. When that is removed they are adrift. I believe the He plot could potentially go a long way in building empathy among men for what society does to women. Perhaps by relating to it via a male character, it can lead to men realizing it should be abolished.

I don’t have too much to say about the Sebex other than the fact that I believe they represent a growing acknowledgement that gender and sexual attraction are a lot more of a fluid spectrum than we’ve been taught so far. Sure, there may be many people who will always be at the extreme ends – fully gay for life or fully straight for life (and the same with male and female). But there are many in the middle who go back and forth as situations and emotions dictate. And within gender we have everything including cross-dressing, identifying as another gender, but keeping one’s body, and identifying as a different gender and taking the steps to become that body. So in addition to helping Matt Fraction with the plot, I think it works as a great metaphor.

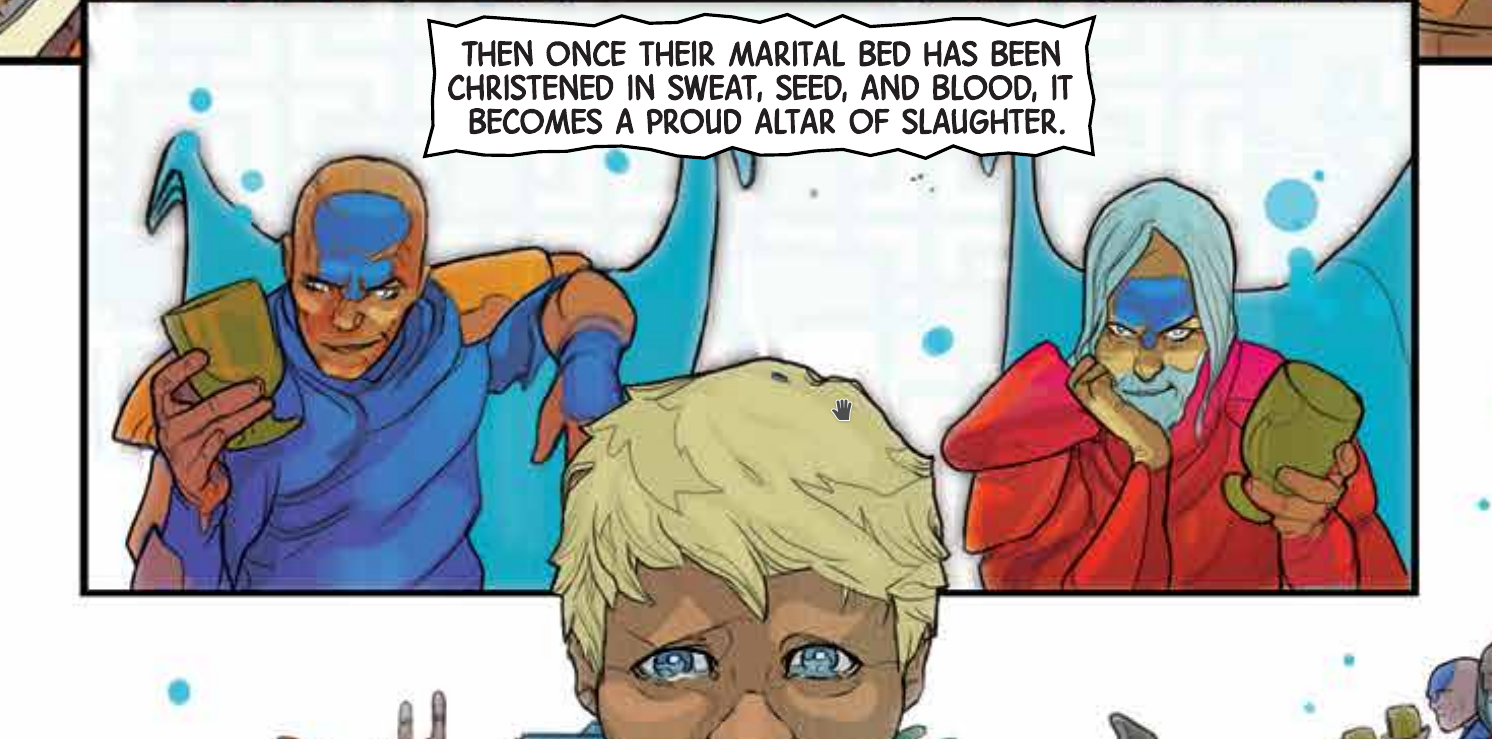

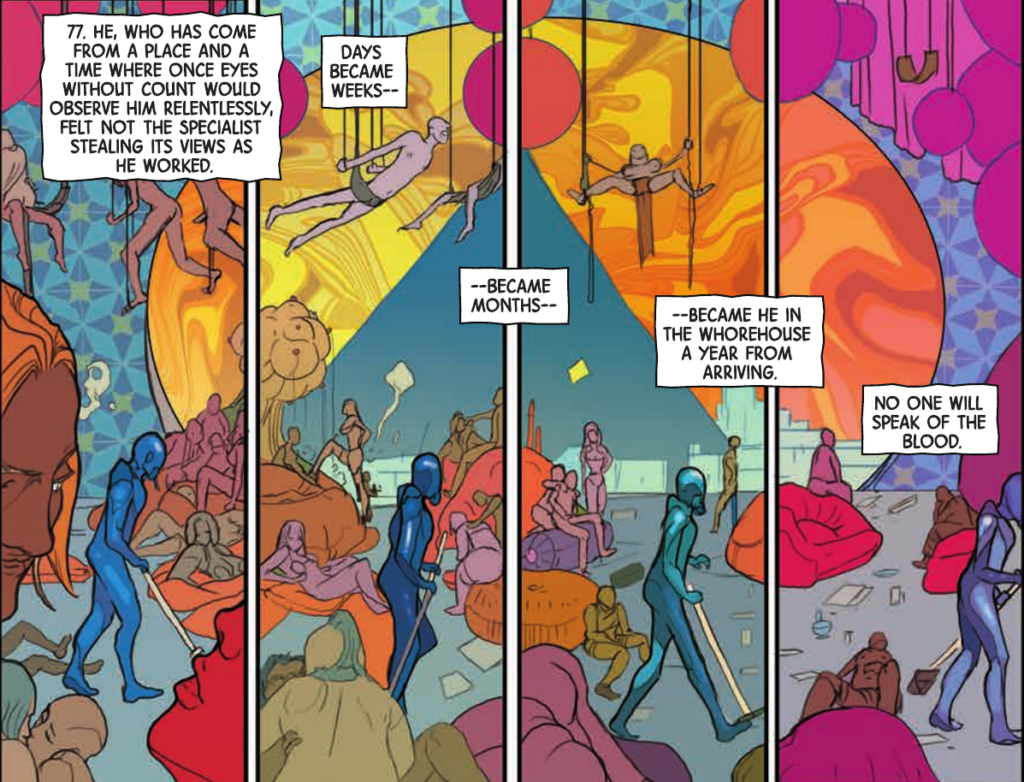

On Q’af we have a tale that was either the inspiration for 1001 Nights or happened to arise independently with about the same plot. The brother-kings of Q’af are cuckolded. Their vengeance is that every night they sleep with citizens who have come of age. After the rape, the citizens are murdered. This is so that no one can ever cuckold them again. Eventually, some characters end up there who forestall their murder by telling a story. In Fraction’s version, one brother is heterosexual and one is homosexual and I believe this changes the dynamic slightly over a situation where they were only taking wives. In that case it would be the same male over female domination that has existed almost everywhere almost throughout all history. (I’m sure there’s at least one society that was flipped) In this case it is all love that is viewed with suspicion by the brothers. Not the same old story about women being untrustworthy. Instead it’s EVERYONE ELSE who’s untrustworthy. The brothers are left only trusting in their familial bonds.

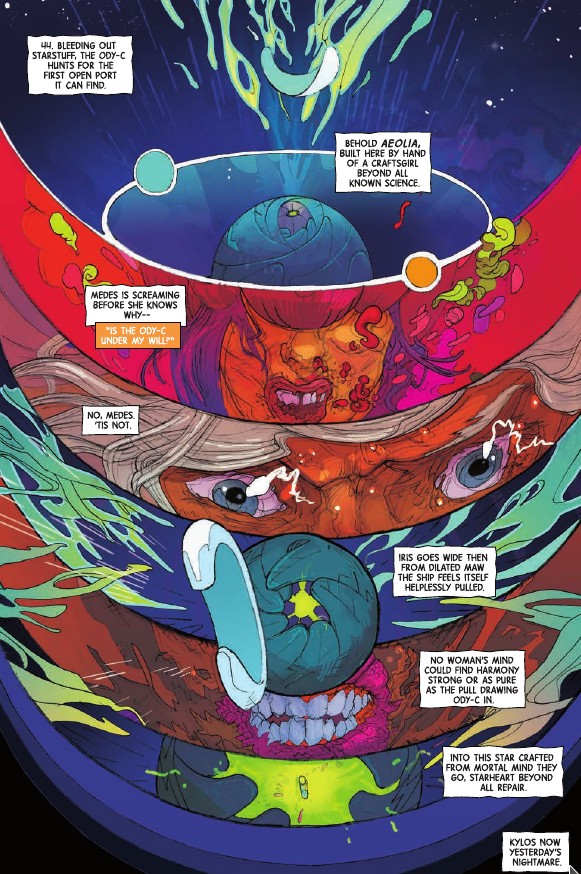

Finally, there is Odyssia’s ship. Of course, the most powerful and amazing thing about women is childbirth, the power to create life. This is why the early humans originally worshipped goddesses. And so Fraction and Ward imagine a ship powered by Odyssia and her crew inside of womb enclosures that allow them to communicate at the speed of thought. When I first read the section in the first chapter where things go awry in the ship when one of the crew is out of sync with the others in terms of her thoughts, I originally thought it was perhaps a commentary on groups of women. That, because women tend to be relationship-based, it was a comment on harmony and the effects of women being in disharmony. (For example, how men tend to try to outcompete each other while women will use social punishments against their enemies) But as I revisited the scene to work on this essay, I began to think that while this scene might work in this way, it is not necessarily about women at all. When the Odyssey was written, navies were made up of boats that were rowed by large crews of men. And if you’ve ever tried to row a boat just with a few people, it does not work if everyone is in perfect harmony. I was briefly on the rowing team during my undergrad and there was a vast difference when we were in sync – just one person could throw things off mightily. And so while there are aspects of the ship Fraction intentionally designed to spur commentary, other aspects would likely be the same regardless of the gender or genders used in the story-telling.

I feel very conflicted about how well this book has come together. On the one hand, Ward’s art truly elevates the book to the level of art (who is left to say that comics can’t be art on the same level as the best prose books?). On the other hand, it makes an already difficult story even more difficult to comprehend as sometimes the reader is fighting the art while trying to figure out the narrative. But if it can reach more people with this timeless story and use the gender flip to get more people to think outside of their own experiences, I think it’s an overall success.