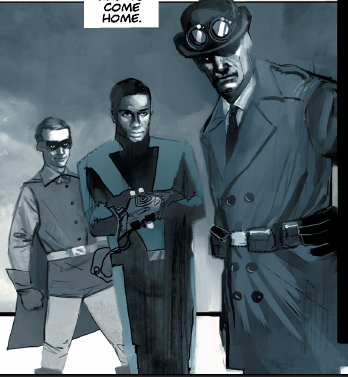

Two things attracted me to C.O.W.L.: the subject matter and the author. I knew Kyle Higgins from Nightwing Vol 3 (AKA New 52 Nightwing) where I enjoyed his writing. C.O.W.L. takes place in Chicago in 1962 when unions are still strong and the Chicago Organized Workers League (C.O.W.L.) happens to be the superhero union. Similar to Watchmen, and very in vogue right now, the heroes are not pure of heart; some of them are just shy of being sadists.

The main plot of Watchmen is two-fold, someone is investigating hero murder and someone is trying to create a tragedy to unite humanity and end the Cold War. But knowing that doesn’t take away from the story, which is a deconstruction of Super Heroes and is focused on their stories and personalities. Similarly, the main plot of C.O.W.L. is a negotiation with the city about whether to continue the contract with C.O.W.L., but the story is about the characters Higgins has created. If I may continue the comparison for one more subject, I’d say that both Watchmen and C.O.W.L. benefit from being self-contained stories of about the same length. It allows Higgins to focus on the story without worrying about the long-term implications for his characters.

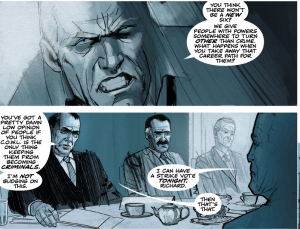

We tend to take it for granted that those with super powers (especially if they aren’t gifted in tragic circumstances) become heroes. There are very few stories in which those gifted with powers decide to simply take because they can or use their powers for selfish gain. Heck, we rarely see heroes for hire (despite a perennial Marvel title with that name). This is why it hit me so hard when the head of C.O.W.L. mentions during negotiations that one of the benefits to the city of Chicago is that C.O.W.L. gives super humans a productive way to use their powers rather than turning to crime. I’d never thought of it that way before – our classic heroes and villains tend to be pretty black and white. The villains were either criminals before their got powers or felt they were wronged by society and heroes just chose to be good. Most of the good guys have regular jobs for their regular human personas, but what about the supers in a bad economy? Would they simply let themselves starve? One of the oldest ethics debates I ever remember having is when it is OK to steal – like for sustenance. What if your powers meant you’d likely never be caught, wouldn’t you use them to make sure you didn’t die? And once on that slippery slope, might you simply use your powers to become middle-class?

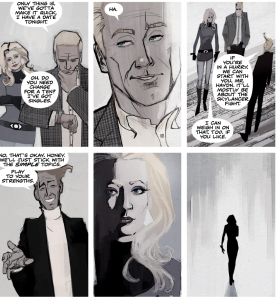

Setting the story in 1962 allows Higgins to explore unions at the pinnacle of their power, but it also allows him a significant B-story about sexism. The 1960s were a weird time for women in the workplace. World War II had taught them they were just as capable as men in the workplace, but Eisenhower’s America needed them to go home so that the economy could absorb the men who’d come back. But their daughters were having none of that and found themselves in a world that was begrudgingly accepting them while treating them with condescension. After all, if women were equal to men, where had they been all these years? (Of course, ignoring that women not working was an anomaly when viewed against the whole of human history) Radia, the seemingly sole woman in C.O.W.L. finds herself in the especially frustrating position of being treated like a woman in the workplace while having super powers, making her stronger than most men. I don’t want to spoil how she deals with this issue because it ends up playing into the narrative in a few key points, but it’s definitely an idea that Higgins explores rather well.

And now we arrive at the crux of this book, the negotiations between C.O.W.L. and the city of Chicago. There will be spoilers here, but as I said before, I don’t think they take away from the actual story and characters of C.O.W.L.. As I mentioned above, it’s rare for super heroes to find employment as super heroes. Most of them are essentially moonlighting as heroes and some of the drama in their book comes from that balancing act. The closest two I can think of are the X-Men and the Fantastic Four. The X-Men are employed because they are supers, but not to be supers. Officially, they’re employed as teachers. The Fantastic Four similarly are all working for a foundation, but I’ve always been under the impression that their income comes from Reed Richards’ inventions or other scientific contributions. So why is it that we never see super heroes getting paid for being super heroes? Well, for one thing, it doesn’t jive with our image of hero purity. The bad guys are in it for the money and the good guys are in it for justice. But C.O.W.L. reveals a different issue with heroes getting paid to be heroes – unintended consequences.

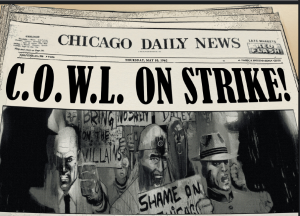

Channeling a lot of what’s been in the air over the past decade or so, Higgins essentially sets up C.O.W.L. to be a unionized government contractor. As super villain crime has fallen, the mayor of Chicago is under pressure to negotiate terms that are more favorable to the city at the expense of C.O.W.L. Unions have really only one real bargaining chip – to strike. So C.O.W.L. orders its supers to strike in order to get the city to meet its demands. It has to do this in order to do what’s right for its employees and keep them gainfully employed. But it’s one thing when car factory workers strike, it’s something entirely different when public safety officials strike – people can get hurt or die. And so this radically changes the super hero equation. Imagine Superman letting Lex Luthor take over the world unless his bills are paid.

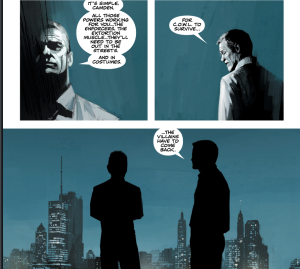

But the incentives become even more perverse. There will always be fires and petty criminals. But if there are no super villains, what does the city care if super heroes are on strike? So the head of C.O.W.L. makes a deal with a mob boss who’s been employing super villains to make sure the villains wear costumes so they are recognized as super villains. In a nutshell, this provides the leverage C.O.W.L. needs, but at the expense of terrorizing the public.

There are lots of other small subplots within these eleven issues (or two trades) that make it worth reading – Higgins has created a fascinating world with very believable characters aided by popping art by Rod Reis and Stephane Perger.

I enjoy discussion, so join me wherever you happen to read this.

C.O.W.L.: Principles of Power and C.O.W.L.: The Greater Good by Kyle Higgins and Alec Seigel with art by Rod Reis and Stephane Perger. (Help support Comic POW! by buying from these links: C.O.W.L. Volume 1: Principles of Power and C.O.W.L. Volume 2: The Greater Good (Cowl Tp)