Here at Comic POW! because we’re not obsessed with reviews and are, instead, looking at greater themes within the works, we’re able to revisit older stories along with the newer stories. So this blog post kicks off a series focusing on Bill Willingham’s Fables.

There has been a huge resurgence in interest in the stories of the Brothers Grimm. On one side we have Disney revisiting their animated films as live action films (as well as others leading to two Snow White films in one year). On the other side we have TV shows like Once Upon a Time and Grimm. But before the ABC show thought of what it would be like to have characters from our fables among us in the real world, Bill Willingham was telling a similar story nearly fifteen years ago.

Story

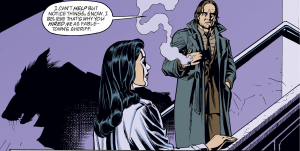

The first story is set up as a Whodunnit complete with a Parlor Scene. It’s a great way to introduce us to the main characters and the situation the Fables are in without uncharacteristic exposition. Things that need to be explained make sense within the context of an investigation. The one time that something is mentioned unnaturally results in a lampshade hanging – Snow White tells Bigsby Wolf that she knows who her sister is when he states the fact to her for our benefit. That kind of cleverness run rampant throughout these two volumes. What is originally thought to be the murder of Red Rose turns out to be a scam to get money to pay for her boyfriend’s failed business.

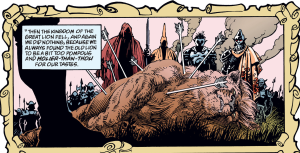

The second story is titled Animal Farm and it is, in a way, a re-imagining of George Orwell’s classic story. As we learn in the first story, the Fables that don’t have a human appearance have to stay on a farm in upstate New York. Some of the animals resent this and plot a takeover of the Fable Government in order to be able to live in Manhattan. The first volume introduced the idea of a sect of the Fables who wants to make themselves known to the humans, known as the Mundanes or Mundys for short. Those fomenting revolution on The Farm are, in a sense, a militant wing of this sect – radicalized because of their segregation. Eventually Snow White and Red Rose discover the treachery and prevail.

Themes

Within these stories Willingham is not just creating fractured fairy tales in the vein of Shrek and all its imitators. Instead he has created a a complex mythology in which to play out his ideas. Perhaps most refreshing is the fact that his characters and settings do not limit themselves to any one genre. Already in the first two volumes he has created a Whodunnit and a revolutionary tale.

The first theme I wanted to explore involves the character of Snow White. We media critics often throw around the phrase “complex character” quite a bit. However, I think this is almost an understatement when it comes to Snow White. She is complex ALMOST to a fault. While I only these two volumes (which I’ve read twice) to guide me so far, I’m left constantly teetering on whether I find her characterization to be somewhat schizophrenic or just real in a way we rarely see in media. When we first meet Snow White, she is dealing with a distraught Belle and Beast. The stress of marriage causes Beast’s human form to revert somewhat to his beast form. Snow White is fair, but ultimately tough as there is not much she can do to help the situation. When it comes to her dealings with Bigsby Wolf, she is, again, tough and doesn’t let him push her around. Within the first volume, her crying at her sister’s apparent murder makes perfect sense. Even the most hard-assed person is still a person. She also comes up with a complex punishment for everyone involved that allows everyone to end up in peace and placates Bluebeard. But in the second volume she seems woefully clueless in both assessing the situation on The Farm and in her troubles in trying to free Weyland Smith. It’s like she took a stupid pill that weekend or something.

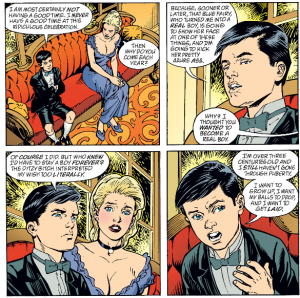

Before I head into some heady material, I wanted to comment on an interesting device Willingham creates which leads to interesting and complex relationships among the Fables. He decided that every character with a shared name across is the same person. Some examples I picked up on: Prince Charming was married to both Snow White and Cinderella; Snow White is both the Snow White who lives with the Seven Dwarves and the one who has a sister named Red Rose; The Wolf is the same in every fable with a wolf.

Anyone who has been involved in comic book fandom for long enough knows of a problem shared between comics and soap operas – nearly no deaths are final. Even Bucky who used to be counted along with Gwen Stacy and Uncle Ben among those who could never be resurrected came back with the Winter Soldier storyline. A few stories recently have taken a strategy similar to the one in Fables, but I think more stories of death and resurrection would have more punch if they did something similar to what Willingham does in the Animal Farm storyline. In this story Snow White is shot through the head. She doesn’t die because, similarly to the way gods were dealt with in Small Gods, she is loved by too many people in the world. However, she doesn’t just wake up and everything is honky-dory. She is in the hospital for a long time recovering from her injury. There are consequences and pain and suffering for her death even if it’s not final. This keeps the stakes high when life is on the line in this series. Also, if a character is not known to be famous, their death may be permanent.

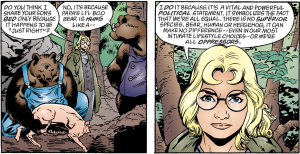

The biggest theme of this series is, of course, the theme of an Exile Community. I could see this comic, if translated to the local language, being quite popular with exile communities around the world. Like exile communities everywhere, there are many things they struggle with. For one, when do they try to take back their lands? Are they even able to take back their lands? Second, do they assimilate into the new world or remain separate? And, in remaining separate do they maintain their ties to the old lands? This is broached in the auctioning of the titles to Prince Charming’s lands. People are willing to pay for it even they have no idea when they’ll be able to go back to it. Third, even if people were rich in the old lands, they may be struggling for money here because they weren’t able to bring everything with them. History is littered with tales of those who lost everything escaping a war. There are echoes of the Jewish and Cuban exile communities with a toast that next year they’ll be toasting in the old lands.

There’s also a pretty blatant adaptation of the “First they Came….” statement from Neimoller as they explain how they were originally too selfish to help each other out when The Adversary was taking over their lands.

All Fables have immunity for what they did in the old lands. Willingham uses this to explore ideas of forgiveness and recidivism. While people are not supposed to act upon the biases of what went on in the old lands, when push comes to shove they make accusations that perhaps people have returned to their old ways. It is true that people never seem to be able to shed their old reputations even if they have entirely cleaned up their acts. Yet our main characters have to put these differences aside for the greater good.

Although Willingham only explores this through two throwaway situations, he does bring up the concept of the tyranny of a lack of aging or change in situation. The first is during the Beast and Belle scene where they complain of being married for centuries. The second is when Pinocchio complains of always being a kid. While certainly not a new idea, it is often a great reminder that the wishes we have as time-bound people might not be our wishes if we were truly to live forever.

The Animal Farm storyline touches on a lot of things that are brought up by war fiction that isn’t meant to be wish fulfilment fantasy. For example, the fact that sometimes people are killed simply for having the wrong ideas. Also, sometimes people go along not because they believe in the ideals of the revolution, but because they want to keep from being killed in a “you’re with us or against us” situation. But it also makes allusions to the fact that many revolutions have, at their core, a member of the privileged class helping to support the war. For example, Goldilocks could be a Che or Castro analogue. As professionals, they would have benefited by leaving things capitalist in Cuba. Similarly, Goldilocks doesn’t have to care about the farm as a human. Of course, because (as in real life) motivations are messy and complex, there’s also the fact that she is sleeping with (a grown up) Baby Bear. There’s quite a bit of interspecies flirting (and more) going on in this series, but not enough in these volumes to merit its own paragraph.

Finally, I’d like to note that it’s refreshing that there appears to be a lot more beefcake than cheesecake these two volumes with both Wayland and Bigsby Wolf appearing in states of undress while only Rose Red appears to have any titillating drawings.

I’ve love to discuss what you think in the comments below and, since these volumes are old – spoilers for these volumes are fine. (But don’t spoil future volumes, please!)

Fables: Legends in Exile and Fables: Animal Farm by Bill Willingham with art by Lan Medina, Steve Leialoha, Craig Hamilton, Sherylyn Van Valkenburgh with letters by Todd Klein and covers by James Jean and Alex Maleev.