Most writers have themes they return to time and again, each time looking at a different way. This also is true of many of the most lauded comic book writers. Alan Moore is fond of using public domain characters and exploring politics and the deconstruction and reconstruction of super hero tropes. When working with established characters, Grant Morrison can’t seem to get enough joy out of mining a character’s past continuity to find new ways of making what is often a discarded, silly part of the Golden or Silver Age canon bring new light and understanding to a character. Morrison also likes to explore the metaphysical, leading to dense comic writing that can be hard to get through, but rewarding if you get all the references and points he’s making. He also likes to look at the future consequences of today’s actions, most famously during his runs on New X-Men and Batman. Mark Waid has become the master of exploring the consequences of lies and the truths we withhold from each other. His heroes have secrets even from each other and that can lead to dire consequences. Finally, we have Jonathan Hickman who seems to have two primary themes that run through his work. The first is about the role of fathers and the effects of having/not having a father and having/not having a family. He has explored this in more than one comic, but it is the central theme of his excellent run on Fantastic Four and FF. I would love to see another writer run with the fact that Hickman has Valeria choose Dr Doom as her father figure. Hickman also enjoys exploring how a cabal of very intelligent people can radically change the world. This was a minor theme during his run on Fantastic Four, but it is a central theme in S.H.I.E.L.D., The New Avengers, The Manhattan Projects and East of West.

The Manhattan Projects, which we’ve covered before in the old challenge format of this site (and a commentary will appear next week), is a world in which the development of the atomic bomb was the least important and least radical thing being done by the group of scientists in the south west of the United States. Things continue to spiral into a radically different version of history as the scientists discover space travel, teleportation, and AI.

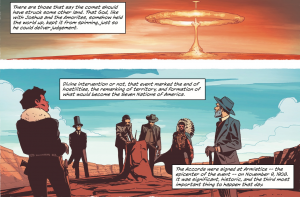

East of West is starts off with normal history and then, during the American Civil War, a meteor strikes Earth. Control of the USA splits into seven nations – Union, Confederacy, Texas, Chinese (PRA), Native American nations (The Endless Nation), African American (The Kingdom), and I’m slightly unclear if Armistice is considered the seventh. A cabal of leaders – mostly the leaders of the Seven Nations at the time of the armistice – also write The Message. The Message is a Revelation-type prophecy for bringing about the Apocalypse. For some reason the cabal sees this as a desirable thing.

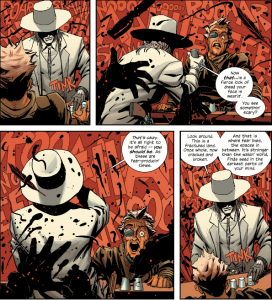

It has become cliche to say that something defies categorization, but never has this been more true than when considering East of West. As we’ve already discussed, the book is a alternate history. It also has a very western feel and vibe to it – especially with the character designs of Death and Chamberlain and the themes of justice. It concerns the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and contains many religious themes. An entire issue is devoted to what can only be seen as a deconstruction of protests movements and the fallacy of democracy. East of West also takes place in the future, 2045 or so and Nick Dragotta has given it an aesthetic akin to the manga/anime Trigun. Death’s initial plot and even the first flashback scene we see in the first issue are reminiscent of Kill Bill. In fact, as I read the comic I found myself wishing Tarantino would direct an HBO show based on East of West. I rarely want comics to be converted from the page because of the changes that have to be made to the way the story is told, but East of West is one of the first non-Batman comics where I hear the characters speaking because they have so much character. It would also be pretty amazing if it was made into a cartoon so it could most match the comic’s aesthetics. Could be pretty groundbreaking, I think. But enough gushing.

The Kill Bill comparison is quite apt as the series starts with Death looking to get revenge on those who beat him and took something from him – just as The Bride is beaten and her baby is taken from her. He also reveals that he must be called in order to do his appointed function. I love the British humor in Terry Pratchett’s Death from the Discworld novels and Good Omens, but Death as a cowboy on a revenge mission may just be my new favorite incarnation of death.

It’s also interesting to see that the other three of the Four Horsemen have been reborn as children. They were clearly expecting Death to be with them and decide to kill him when he’s not there. The horsemen mention that when they resurrect they start out as children and also that they may not be the same sex as they were before. Hickman always makes brilliant use of the themes of color in his books (moreso in his Image books) and a VERY good commentary series I read mentions that in the Bible, the Four Horsemen are also of four colors. Although I am not sure if we’ve seen this yet by this point in the narrative, I think it’s interesting, but has not yet been revealed why, that Death used to be black. He is white in his current incarnation. Clearly, this is important symbolism and, at its most basic I think it has to do with the fact that he’s on the side of good (relatively speaking).

As we move forward in the series we continue to explore Hickman’s themes of love, family, and fatherhood. We learn that Death fell in love with one of Mao III’s daughters, Xiaolian (which means fillial and incorruptible). Her sister, Hu, is one of the Chosen and the other horsemen convince Hu to attack her sister and kidnap the baby she had with Death. When it comes to fatherhood, Mao III is disappointed with both his daughters for opposite reasons. Hu was impulsive and angered Death. But Xiaolian was also impulsive in cultivating a relationship with him. A father’s love for his daughter is powerful, however, and he has been visiting Xiaolian even though she had been imprisoned by her sister. Love is powerful enough to make Death try to give up being a horseman and just be a father. This upset the other horsemen because all four of them were necessary to bring about the Apocalypse.

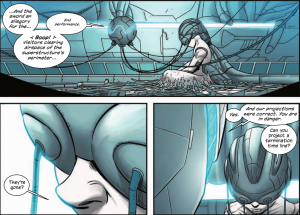

Jumping around a bit, we eventually see Death’s son who is The Beast mentioned in Revelation. He is growing up without a father, but he does have a training robot serving as a father figure. It reminds me a bit of Kid Apocalypse in Remender’s run on Uncanny X-Force. In what I think was one of the key reveals (but which even that great commentary missed), The Beast is actually pretending to be schooled in destruction when he is under observation, but he is actually plotting a way out. We also see the length a father is willing to go as Death journeys deep into a prison holding a blind Oracle in order to find his son.

In our culture we have a great deal of examples of bargaining with Death in an attempt to cheat death. It is so pervasive that Colbert makes fun of it in the graphic to his segment Cheating Death and The Sims 2 allowed the player to play rock, paper, scissors with death if one of his characters died. So it is quite powerful against that motif to see Death promising ANYTHING to the Oracle if she will reveal where his son is. She exacts quite the payment from him – an eyeball as a replacement for the ones that the horsemen took from her. Quite a body horror moment! And she tells him he will pay an even greater price for more information about his son in the future.

One of the best things Hickman did in Fantastic Four was to bring Sue Storm to the fore. She is revealed to be the linchpin of the team – she is what keeps Reed Richards grounded. She is a moderating force for Johnny and a compassionate force for Ben. Hickman was probably not the first to make her strong, but he certainly has her hold her own. In East of West we see an interesting maternal relationship between Ezra Orion and Conquest, who was a woman in the previous incarnation. For unexplained reasons, the Four Horsemen slaughter the pilgrims every time they come to worship at Armistice. During one such slaughter Conquest saves one child and raises him as her own. She plays the role of the mother who is never quite satisfied with her son’s progress. Constantly asking him if he can do better. She is finally satisfied when, as a living metaphor, his quest for approval has led to his constant pain, horror, and eventual death.

The second set of five issues has Hickman delving further into the relationships and backgrounds of the various Chosen – both among each other and with their families. The final important family relationship is between John Freeman and his family. The king has sired so many children (14) that he has forgotten and has to ask an advisor how many children he has. He has a purely darwinistic attitude to his children as well. When he feels that John Freeman (crown prince and member of the Chosen) is perhaps faltering in his resolve or may have loyalties to “his religion”, he threatens to merely replace him with one of his brothers as next in line for the crown. As if to underscore how interchangeable they are, each of his brothers is named John Freeman as well. In fact, John Freeman the Ninth challenges him to battle in a attempt to eliminate those in line before him for the crown. John (the Chosen) blasts off John (the Ninth)’s leg and spends the next two issues calling him “Three Quarters”. The king ultimately uses these two incidents as a teaching moment for John and we see the father-son relationship as the strict mentor who wishes for his son to be the best. There is no compassion or it is masked.

This also brings up an interesting point, while there is a member of The Chosen in each of the Seven Nations (I would be remiss in not reminding the readers of the Biblical significance of seven as completion), not every country is run by one of the chosen. In the case of the PRA (pre-issue 3ish) and The Kingdom, it is the children of the leaders who are involved. In the case of The Confederacy, it is an adviser. In the case of The Endless Nation, they have banished their Chosen, Cheveya. Also, a great time to note that I love that The Endless Nation is the most technologically advanced of the Seven Nations. So they truly are a cabal rather than merely the heads of state getting together to bring about Armageddon.

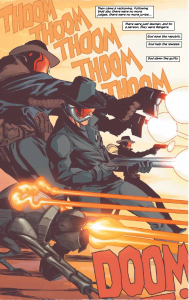

Hickman also seems to be setting up a “your princess is in another castle” situation for Death. For one thing, The Beast is plotting how to escape. Second, in a pretty amazing issue in which Hickman deconstructs Judge Dredd we see the Texas Ranger take justice into his own hands.

The mask he and other Texas Rangers wear as they battle the corrupt judges cannot be mistaken for evoking the comic from 2000 AD. But, unlike Dredd, the Rangers realize that they need to give up their powers lest it corrupt them as badly as it did the politicians. When Bel Solomon (great, evocative name just like Ezra Orion) realizes he no longer wants to bring about the apocalypse, he asks the Ranger to come out of retirement to kill The Chosen. So there are two new variable that could make Death’s story extra tragic if he gives us so much to the Oracle only to find that his son is not where she said he’d be and/or that the members of The Chosen he needs to interrogate have already been dealt death blows by the Texas Ranger.

I’d like to conclude the story portion of this article by mentioning that Jonathan Hickman is the master of planning ahead. He came to Fantastic Four with nearly the entire (3 years, I believe) run plotted out. This pays dividends as it allows Hickman to place layers upon layers of information into his comics that reward the reader upon multiple reads. For example, early in the first issue when the bartender realizes Death is before him, one of his eyes pops out of its socket from beneath an eye patch. At the time it appears like a strange Looney Tunes effect. But I didn’t yet know the rules of the world or the tone of the comic, so perhaps Hickman wanted some slapstick with his drama. Then, nearly a year’s worth of issues later, we realize that the bartender (now known to us as The Tracker) is in posession of one of the Oracle’s eyes.

Throughout this article you’ve seen the examples of the great artwork from Nick Dragotta (pencils and inks) and Frank Martin (colors). It’s easy to take their work for granted because they do such an amazing job that their work just moves to your subconscious. In the three years since I’ve returned to comics, I’ve seen a lot of artists. Some are great at backgrounds; others on the human form. Some can portray action well. Others can actually make you feel what these fictitious characters are feeling simply by viewing their facial expressions. Dragotta, in East of West, does all of these things brilliantly. The backgrounds change from extremely detailed to just a painted rectangle as necessary for the story. And the slaughter that occur within these pages, also quite a difficult thing to get right, looks incredible.

Additionally, his choice to make sound effects such a huge background element creates an almost surreal element as it evokes the sound being so powerful it overwhelms the need for any background image. The earliest example is during the scene of slaughter at the bar in which the sound effects (of people screaming in terror) do a better job of conveying the horror than anything that could have been shown in a series of panels. The brain fills it in and the brain is capable of true horror. But one cannot overlook the part that Frank Martin plays in all of this. He has chosen the perfect palette for this series. The color tone can really make or break the mood of a comic. With The Manhattan Projects, for example, I think the lighter palette serves as an excellent counterpoint to the horror on the page. It helps lighten the tone and it goes well with the sarcasm and hyperbole of the series. That would be disastrous with East of West which is essentially a sci-fi western and needs to thrive on the dark humor of the genre. It is self-serious and it needs to be. The Manhattan Projects revels in its ridiculousness and it gets a color palette to match.

After these first twelve issues, it seems that Hickman has set up all the dominoes and shortly they’ll begin to fall. I can’t wait to see how things begin to resolve. As I mentioned, there are now two complicating actors, Texas Ranger and The Beast, in addition to the treachery and trickery of many of the members of The Chosen. I’ve only touched upon the highlights of the story. There are many small moments you need to see. Hickman, Dragotta, and Martin are creating a masterpiece – depending on where the story goes, this could be the next Watchmen, Sandman, or Killing Joke: a comic that is a classic-must read. If you like science fiction, westerns, or vengeance stories, you need to be reading East of West.

This is a pretty deep story and I’d love to discuss theories, allusions, and metaphors with you in the comments below.

East of West written by Jonathan Hickman with art by Nick Dragotta, colors by Dean Martin, and letters by Rus Wooton. Get the first two trades on Amazon (East of West Volume 1: The Promise TP

, East of West Volume 2: We Are All One TP

) or Comixology (Vol 1, Vol 2). Get single issues DRM-free at Image Comics.

[…] week we explored the major themes in Jonathan Hickman’s East of West. This week we continue with another Hickman series, The Manhattan Projects, and this […]

[…] manga-cartoony, the colored version definitely feels less “real” to me. With my look into East of West I spent some time talking about how colors can affect the mood of a book and how Hickman has two […]