Saga resumes today and, combined with the Humble Bundle sale which included Volumes 1 and 2, I think it’s as good a point as any to examine what Brian K Vaughan is saying with Saga as it moves into its next phase in which our narrator is a toddler. After all, Y: The Last Man, Vaughan’s previous original story, is no more about a world in which one man is left alive than The Walking Dead is about zombies. In fact, I’m behind on The Walking Dead, but at the point at which I’ve stopped, no one knows why it happened and Kirkman seems in no rush to tell us, if at all. Similarly, Y: The Last Man left the reason behind the deaths up to the reader.

So what is Saga really about? On the surface, and on the most basic level, it is a cross between a maligned mixed marriage story and a run or die story. Of course, this is the driving force of the plot. It’s certainly one type of plot to have Hazel have parents of different races. It would up the ante if the races were simply at war. But to have the government itself after them raises the stakes to a much higher level. And that results in the introduction to the first layer of what Vaughan is asking us to think about.

Humanity, for whom the characters of Saga stand in, requires something important for war to exist on any sort of extended timeline – the enemy must be other. Everything we are, they aren’t – and vice-versa. During World War 2 our enemies were considered subhuman. Although the phrase, “In God We Trust” had been around since the war of 1812, it was made the official motto of the USA as a direct response to the fact that the USSR was an athiest nation. In Saga the existence of a romance between citizens of Landfall and Wreath would be bad enough for the war movement. A child is anathema. A child is the literal embodiment of the sentiment that there is nothing all that different between the two races. Not only is it a hybrid of the two, but it signifies that the physiologies are so similar, that a child can come of the union. Regardless of how you happen to feel about gay rights in the USA and worldwide, the fact is that the more people you know who are gay, the more you realize – “Oh, they’re just like me, except they like people of the same sex. They aren’t monsters.” If there’s only one, you think – this man (or woman) is an exception. But the larger the numbers, the more you’re forced to realize that we’re all the same. The same dynamics are at play in Saga. It’s why a government would give a damn about a child and would hire bounty hunters to murder her.

Related to this is a bit of a commentary on the free press and the effects that the press can have on propaganda. Vaughan is exploring a slightly different angle on this within his other currently running story, The Private Eye in which the press is functioning as a LITERAL fourth estate for the government in guarantying personal privacy. Within Saga we have Doff and Upsher whose investigation of Alana and Marko’s relationship and child were so dangerous to the government that they were cursed with some magic that would keep them from reporting on the story. It’s an interesting difference from the real world because without magic the only way to silence them would be death. However, at least one of them appears to be trying to contrive a way to reveal the information without dying.

Via Prince Robot IV Vaughan is also exploring the effects of war and with D. Oswald Heist he is exploring pacifism and activism through culture jamming. Prince Robot IV is haunted by the carnage of battle. He wants to settle and just have a family, but his father encourages him to continue the war as part of their treaty. Heist lost his son because of the war and that leads him to turn his pen towards an anti-war novel. Given the dangers of going up against the state, Heist uses a tactic that has been used effectively throughout history in the real world – hide your message in narrative fiction. Not unlike what Brian K Vaughan is doing with Saga although Vaughan does seem to mock the naivete of expecting too much change to come from such work.

Saga is also about exploring the role of military contractors via the idea of The Talent Agency and freelance bounty hunters. The Will, hired by Wreath to kidnap Hazel, but with authority to kill Alana and Marko, is not just a one-dimensional antagonist. Or, in Hazel’s narration, “He’s a monster, but some monsters are worse than others”. He frees the Slave Girl when he goes to Sextillion for some … relief … and finds out this girl is being forced into sex slavery. However, he seems to be Vaughan’s example of “I was only doing my job.” He’s been paid to kidnap Hazel and whether or not that causes pain, suffering, and death to others – it’s nothing personal. The same could be said of Prince Robot IV, but there’s a key and subtle difference. As part of the military, Prince Robot IV doesn’t have much of a choice. The contractors, however, are doing it for the money rather than more “noble” causes like patriotism or having to because they are in the military.

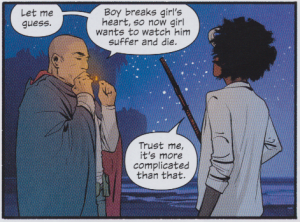

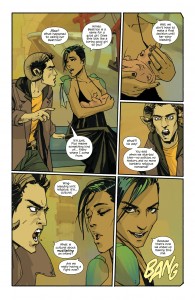

Saga is also exploring the spurned ex/psycho ex. In addition to the dramatic tension added (especially in the issue that ended with Marko mentioning his ex-fiance), it’s a great way of exploring the concept of the past catching up with you. This can happen literally as it does in these tropes in which an ex literally intrudes upon your life. Whether or not you did something wrong (like Marko’s one-sided abandonment of the engagement), an ex can make trouble for a relationship, particularly a new one or one going through extreme stress. Even when the ex isn’t literally there, baggage from emotional, physical, or sexual abuse can cause problems in the relationship. Of course, Gwendolyn also functions as a metaphor for Marko’s past life catching up with him. It’s one thing for the government to be after them, but for people he actually knew to be catching to him no matter how far he runs, that’s a different kind of terror. On the more light-hearted side, it appears that Marko has a type – strong, violent women. Perhaps due to the mother he grew up with?

The biggest reason I started reading Saga after the cover of the issue 1 reprint along with Vaughan’s name drew me in, was the first scene. I’ve seen a lot of births in pop culture (almost entirely movies and TV shows). Saga had the most realistic birth scene I have EVER seen. They seem to want the dramatic payoff of a birth without recognizing the realism. Saga does not make the mistake of over-exaggerated labor pains. Hazel is all bloody and gross when she comes out (not the clean babies we see on TV) Marko is crying (as many men do) at the beauty of the child they’ve created. Alana immediately puts Hazel to her breast – much more realistic than the passing back and forth that goes on in TV and the movies. I knew right away this was going to be a different kind of story. I think, as of the end of the third trade (issue #18) Saga is more about being first time parents than it is about anything else. Vaughan is exploring all the I mentioned above, but the truest and deepest conflict seems to be in being parents. The most important conversations Alana and Marko have revolve around all the things that worry us as parents. In a way, I see the war and the forbidden marriage as being much more about creating a metaphor for the rockiness of parenthood. Always uncertain of what tomorrow brings, always weary, always tired. While Brian K Vaughan hasn’t made any missteps in the storytelling, I can truthfully say that, had I not just become a parent when I discovered it, I probably would have stopped reading Saga when I had to cut back on my comics expenditures. But Saga speaks to me as a parent in a way I haven’t seen in any other comics.

It is the biggest proof for, and example of, what I have been calling for in numerous reviews in Comic POW!, Comic Vine, and Player Affinity (now Entertainment Fuse). There is a power, beauty, and vulnerability that comes with having children. All comics don’t need to have children (different strokes for different folks), but Marvel and DC are constantly chickening out. They want teenage protagonists so they’re always magic-aging the kids (eg Hope in the X-Men comics). They also don’t let their characters grow and age, but there’s something powerful there. What kind of father would Wolverine be, given his life? What kind of grandfather? There are really only two comics in from the Big Two that I think have tried to do this well. Fantastic Four and Batman and Robin Vol 2. Fantastic Four has always had family at its core so it has done a better job, but still hasn’t fully explored the family dynamic as well (Maybe Fraction did it, I didn’t get a chance to read his run on the book) as Saga. Batman and Robin was quickly moving in the right direction under Peter J Tomasi, but that fell apart thanks to events in Batman, Inc Vol 2. It is protection of his family that makes Marko go berserk and break his anti-violence vows.

So that’s what Saga‘s about so far. I can’t wait to get to my comic shop today to see where BKV takes it going forward.

Saga written by Brian K Vaughan with art by Fiona Staples is available digitally at Comixology and, DRM-Free, at Image Comics’ web store.

[…] Of course, we’ve not the only ones who love Saga […]

Over-exaggerated labor pains? Have you given birth? This is the least realistic birth scene I have ever read or viewed. Very few women orgasm during birth, most are in excruciating pain. It’s idealized nonsense written by a male author who didn’t bother doing any research. The only possible justification for the book’s poorly researched writing in the opening scene is that maybe an alien might experience birth differently, so it doesn’t need to be realistically written. But, no this is definitely not a realistic birth.

It jives with some of the ones my friends have had, but we all have different experiences since we all have different bodies.

[…] her own right, led a panel spotlighting Brian K Vaughan’s work. Of course, the panel covered Saga, but it also covered Paper Girls, We Stand On Guard, and Private […]