The Private Eye, Brian K Vaughan’s indie comic book, is two things at once. It’s primarily a noir private investigator story – a broad who may not be all she seems comes into a PI’s office and hires him for a case that goes deeper than you thought it would at first. But, much like Saga, which could be described as a story about being parents in the middle of a war zone, it’s also a science fiction story. I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: the best science fiction shines a light on the present; this takes many forms. The form used in The Private Eye is the of extrapolating of the present to some future conclusion to show where things might end up if we continue on this path. With The Private Eye, Vaughan takes a look at what might happen if we continue to live our lives in the cloud. Since my other job involves technology, I’m constantly reading the tech press and people on there are always predicting a day of reckoning when we’ve given so much away that we lose all control of our lives. The first issue arrived just a month or two before Edward Snowden decided to do a huge dump of top secret National Security Agency documents, and so the comic has an entirely different feel to it as though we are even closer to the future depicted in The Private Eye than we thought. Of course, the self-sharing to places like Facebook and Twitter that form the premise of The Private Eye are more insidious than any nebulous government agency. You have no control whether or not you are observed by the government, but you are indeed in control of whether or not you post those drunk photos to Facebook. The future of The Private Eye takes place when people currently in their 20s and 30s are represented by PI’s grandfather. Here’s how PI retells the story to Gramps:

The bottom-left panel, in particular certain sounds like something I’ve heard over and over again whenever I have mentioned the dangers of over-sharing. People believe that they have nothing to hide and there’s no problem with sharing. But they forget two key things. First of all, you don’t often realize how easy it is to string together data about you from various little shreds you’ve left online. Second, you don’t always share everything with everyone. The first point is well illustrated on this site: Actual Facebook Graph Searches. It’s a fascinating look at how seemingly innocuous likes could lead to embarrassment or even imprisonment. In the former category are searches that link together mothers of Jews who like bacon, employers of people who like racism, and Mothers of Catholics from Italy who like Durex. In the latter category family members of people who live in China and like Falun Gong or Islamic men interested in men who live in Tehran, Iran. If that’s something a comedian can put together, imagine a repressive regime or someone who really wants to cause you emotional harm. On the second point, we have finally reached that point that the only people who don’t restrict what they share on Facebook are those who just joined, cannot fathom the future consequences of present actions, or lack common sense. If you partake of illegal drugs or underaged drinking, you probably only share that with your friends, not all of Facebook. But, what if, as The Private Eye posits, someone breaches that and spills all of your private details out to everyone and suddenly you lose your job, spouse, or freedom. There’s nothing inherently wrong with sharing via social networks, but hopefully readers of The Private Eye will come away realizing that they may need to dial things back a bit if they want to keep their privacy.

Another thing that’s faded into the past without resolution is the fact that search histories are so powerful. When The Patriot Act was passed, a lot of librarians tried to get people to realize how important an issue this was, but I haven’t really heard much about it 12 years later. Many libraries, such as the ones at Cornell, took a passive-aggresive approach. They deleted search histories so that if they were asked to comply they would not have any data to give. I have seen a little more attention paid to the private sector when it comes to search histories, but I think we still have a long way to go to get to mainstream public knowledge. A few fringe people have started using Duck Duck Go as their search engine, but it’s far from the mainstream. The problem is that a LOT can be revealed about us from our search histories and the money that insurance companies (among others) would pay for that access is too tempting to resist. Eventually Google and/or some others will start selling that data and you won’t know that you suddenly can’t get insurance because you were Googling about cancer.

Interestingly, The Private Eye is somewhat Steam Punk, only instead of steam, it’s the 1980s or earlier in terms of information technology. The Internet doesn’t exist anymore. I think one of the most powerful things we’ve lost as the Internet has become more commercial is the social norm of having a codename online. Facebook has been the biggest catalyst, but others have been quick to make it the norm to do everything in your real name. That really reduces the ability to use the Internet to explore aspects of yourself that could be unsavory if you couldn’t unshackle it from your identity in the future. For example, high school and college kids should be free to experiment with identifying with communism or even fascism. As long as no one is harmed, there’s no danger in exploring what the ideas mean to you and wearing a Che t-shirt for a few years. Eventually you realize the silliness of your ways and settle into a more normative life – at least most people do. So in the post-Internet world of The Private Eye people walk around in public wearing masks and all sorts of insane costumes. We can now do in meatspace what we could only do in cyberspace. It’s a key part of the main plot of The Private Eye. It’s also one of the details that I can see possibly actually emerging in our society – Cloud Bursting or not. When I attended the Hackers on Planet Earth (HOPE) conference in 2010 there was a huge interest in makeup and clothing choices that can make someone unidentifiable to surveillance cameras. Given their ubiquity in large cities like New York City or London and their increasing deployment to medium-sized cities, I could definitely see this becoming normative. It would probably first appear in protests and demonstrations (since cops are wearing cameras to ID people now) and might become more widespread if there is a huge societal shift as depicted in the comic.

Related to that phenomenon is the idea in the comic that you change your identity and get to wear a mask once you’re an adult. In 2010 Google’s CEO Eric Schmidt said:

“I propose that at the age of 18, you should, just as a policy, change your name. Then you can say, ‘That really wasn’t me; I really didn’t do that! … I don’t believe society understands what happens when everything is available, knowable and recorded by everyone all the time.”

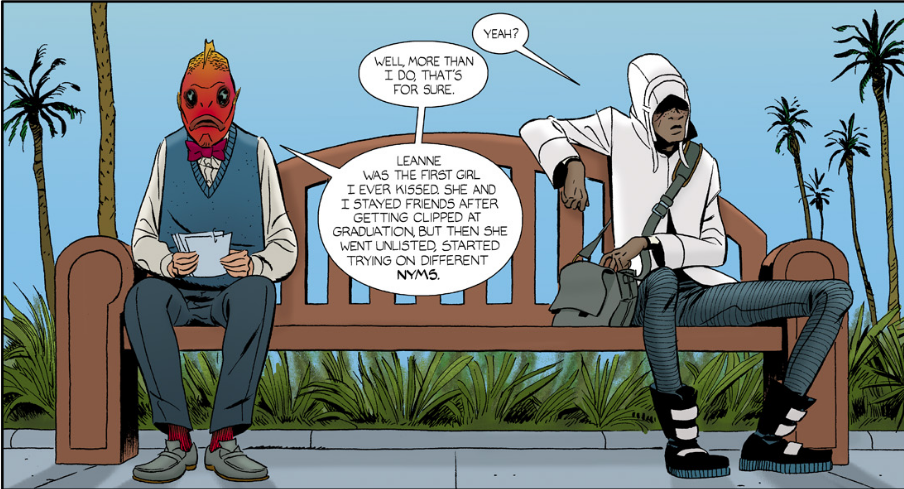

I don’t know if Brian K Vaughan remember that quote (or even heard it) when he sat to write The Private Eye, but its sentiments cover nearly every aspect of the book. PI hires an underaged girl to be his driver and she’s constantly talking about how she can’t wait to get her mask at 18. In the scene above, PI’s client lost track of his high school girlfriend after she started trying lots of different identities. And so we finally get to how PI fits into this new world.

PI is a paparazzi and his profession has taken up the task that was once relegated to the private investigator. However, since privacy is so important to society, having restructured itself after the Cloud Burst, no self-respecting person would have the profession of a private investigator. It’s even more unsavory than the way we view paparazzi in modern times. People hire PI to find information on people who have slipped into anonymity via the masks. He maintains his own set of ethics revolving both around keeping himself one step ahead of the law and also respecting a modicum of his targets’ privacy. For example, he tells one of his clients to forget trying to arrange a face to face with the target. The main story is kicked off when the cliche female client strolls into his office and asks PI to investigate her background. Even though privacy is well protected by social norms and laws, there are still jobs that would do a thorough background check with a paparazzi to make sure they can dig up all the dirt on their potential employees to make sure they can’t be blackmailed. Imagine hiring a PI to make sure that your Facebook profile truly is locked up to just your friends. Or if you’ve deleted yourself from Facebook and other pages on the net – making sure it’s not on the Internet Archive or somewhere else.

On a more meta level, Brian K Vaughan has also anticipated the future of the comics industry. He has taken what Mark Waid is doing with Thrillbent to the next level. At Panel Syndicate Vaughan allows users to pay what they want to any issue – from $0 to any price. (Similar to Humble Indie Bundle and Bandcamp) Other than just supporting production of the comic, Vaughan gives readers an additional incentive to pay for the comics – if you pay more than $0 you can participate in the letters page. While not all comics can work on a model like this one, it ends up allowing users to have more access to the comics and to pay what they think they get out of it. The creator doesn’t care about “piracy”, because that’s just free publicity. The letters pages are full of people saying they read it for free and then went back and paid more than the average comic book because they got so much out of it. Right now I’m on a really tight budget, so it’s a lot harder for me to get into new series if Comic POW! doesn’t have a relationship with the publisher. I was able to get the first issue for free, get hooked, and have been paying $1 since then. It allows me to feel good about paying rather than having to borrow or find the issue online. Sure, I wish I could at least pay the $3 that most comics command, but I just don’t have that money right now. They’re getting more than nothing and Vaughan converts me to an even more loyal fan who will probably bump out other creators’ work if I need to in order to afford anything he does in the print world. (via Image Comics, for example)

Finally, I’d like to say that Marcos Martin and Munsta Vicente’s artwork is pretty incredible. It’s one of the most vibrant and freshest works of art in the comics market today. I’d say it’s only matched in my mind with Fiona Staples’ work on Saga and David Aja on Hawkeye.

Because there’s literally no risk involved to check it out (it can be FREE if you want), I’d suggest that everyone – especially those of us who would be most affected by The Cloud bursting – give the story a read. I’ve taken a heavy focus on how The Private Eye comments on our society and the risks we’re taking with putting everything in The Cloud, but that’s just because a large part of what we do on Comic POW! is critical reading of comics, rather than the same old reviews you can read anywhere. At its core The Private Eye is a great noir romp through a beautifully drawn futuristic world and you can most certainly enjoy it that way.

The Private Eye written by Brian K Vaughan with art by Marcos Martin and Munsta Vicente. You can get it at PanelSyndicate.com

I’d love to chat with you about this, so leave a comment!

[…] I covered the beginning of this story a while ago. […]