It may be cliche to say that art reflects its times, but that does not make it any less true. Mark Millar’s relatively new book, Jupiter’s Legacy, is a book that very specifically speaks to 2013. However, as I’ll get to momentarily, the way we feel now isn’t unique in American (or even world) history and so, depending on which direction the book goes, could end up becoming one of the classics like Watchmen or V for Vendetta which are both very much products of their time, but still stand up today. The book opens up during the Great Depression, after the stock market crash of 1929. Within the first two issues there are a lot of parallels drawn between 1929 and 2008. It’s not perfectly parallel, as I intend to return to later on, but it certainly is the closest the world has come to that moment. Many European countries are still reeling from the Euro collapse and even here in the USA we haven’t yet fully recovered. Folks can debate on the reasons why things didn’t get as bad as they were in the 1930s, but it certainly is the closest that about 3 of the 4 living generations have actually experienced and so we can understand what drives the main characters.

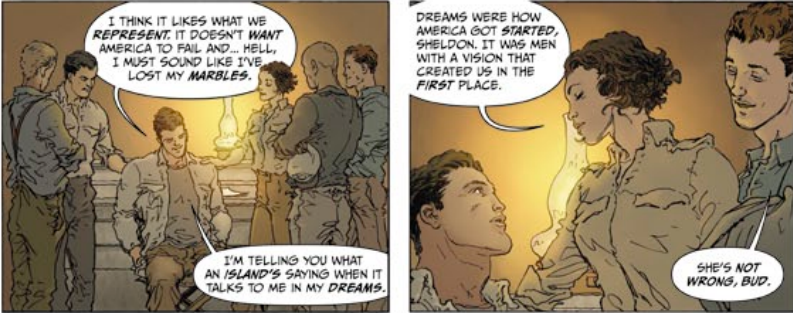

The book takes a very similar tact to Alan Moore’s Top Ten (and this year’s Superman Unchained) by saying that the first super heroes came into the world into the 1930s. It’s always a fun technique – a blending of the reality and fiction. I’m sure that many Americans longed for Captain America and Superman to be real so that we could kick Hitler’s butt and also potentially solve Depression Era corruption. So these fictional universes posit what if it wasn’t just in the comic book pages – what if it actually happened? Also like Top Ten, Millar uses this as a framework to set up the world that most of the first issue and the rest of the comic will inhabit – 2013. We learn that the main characters of the early pages go to some island and then emerge as super heroes. After that we don’t know much of what they did or what happened during those years. It’s largely irrelevant to the story other than the fact that they are well-respected super heroes because of what they did. However, unlike the super hero ghetto of Top Ten, Millar has his heroes continue to reside in America with the rest of us.

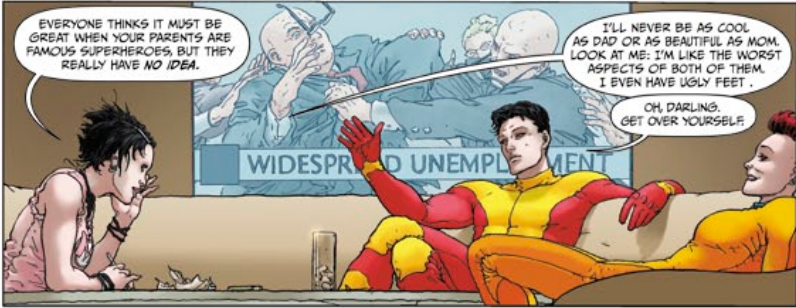

At the point in the story, Millar changes inspirations from Top Ten to Mark Waid’s Kingdom Come. The super heroes have had children and those children are also super-powered. There is a bit of an implication (at least from the way that I read the story) that the supers had sex with each other to produce this offspring. At least two of the characters are brothers, but so far it hasn’t been important to the story nor has any mention been made of what happens when supers have children with normals. (Also, I think there was only one woman on the trip to the island, but let’s not think about those implications) Where Millar departs from Waid is that Waid explores what happens when the supers bicker and become more of a menace to society than the villains. Millar, on the other hand, uses the children of super heroes as a commentary on Spoiled Rich Kids. Just like Paris Hilton and a dozen other children of the rich whom I’ve heard about in the tabloids, but don’t follow and thus couldn’t name, the children seem to be confused and aimless. Like the spoiled rich kids they have celebrity status that rests on the shoulders of those who came before them. It’s both said and implied that many, if not all the children, do no actively participate in any super hero battles. They both exploit their fame and wish to reject it – or at least the circumstances surrounding the fame. They haven’t had to work to earn their trust and they’re adrift – trying various alien drugs, for example. It’s not unlike another Mark Waid work, Insufferable, with the main difference being that the characters in Insufferable are essentially a real-world Batman and Robin so there aren’t super powers to deal with. They and their villains are not world-threatening. Also, the Robin expy grew up as the Robin rather than being born into it.

So as with any great satire, Millar really reaches deep by changing the vapid characters from hotel heiresses to super powered kids. By raising the stakes (other than drunk driving – there aren’t any real consequences of the Hiltons’ actions) he gets us to see the alienation and other emotions that compel these kids to act this way. They’re still spoiled brats, but we can see why.

This scene has a couple of the super kids discussion the fact that all the great battles are over. Their parents have been so successful in eliminating evil that they feel useless. I thing it works as a great metaphor for how all of us feel coming after “The Greatest Generation”. How can we ever match up to that? And, we always say, at least they fought Hitler – it was an easy enemy to fight! It’s not like today where we can debate whether our actions reduce or increase terrorism around the world. Back then people were lying about their age to join the military now people only join because the economy sucks. (Before the 2008 crash, the military had to lower their standards to get people to join) Of course, the truth of the matter is much more complicated. My history studies have shown me that the lead up to America joining World War II was a lot bumpier than we make it seem today. And many of the Allied forces committed atrocities such as raping Holocaust victims. But we white-wash over all that and then feel inadequate when compared to the luster of the glorified past.

Mark Millar pokes a little fun at Spider-Man’s “with great powers comes great responsibilities” motto here by having it come from the older generation. In a lot of ways this is Mark Millar’s commentary on the comics medium as a whole. As we’ve discussed in passing in various articles on this site, comics have been on the move towards the more realistic over the past few decades. As I discussed in my article about Arkham Assylum, there’s less of a tolerance for silliness like the cardboard prisons trope. Similarly, at what point does Batman (or Wolverine or whoever) just need to start killing villains? In a normal justice system, regular people don’t get to repeat offend like comic book villains do. It’s at least part of the reason why I think a lot of people rejected Spider-Man’s “no one dies” claim near the end of Dan Slott’s Amazing Spider-Man run. It made Spider-Man needlessly emo – it’s not as though he was a careless hero. He’s one of the most compassionate heroes out there. And so I think Millar is telling us that Spider-Man’s motto is quaint. Additionally, Spidey earned that motto from a dying Uncle Ben. The kids in Jupiter’s Legacy are hearing it as a lecture.

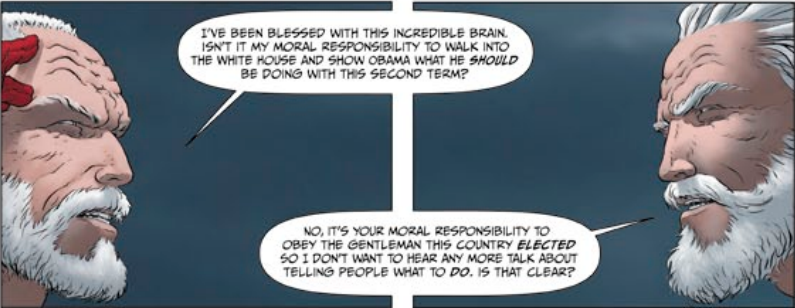

As the first issue ends, Mark Millar borrows from one more person – himself. As I wrote in my exploration of Superman, Mark Millar has already taken a look at what the world would look like if it were run by a super hero: Superman. Of course, with Superman as his protagonist Millar was tied in how far he could take things. Sure, it was an Else Worlds book, but more than anything else it was about how a Soviet-raised Superman would not be all that different from an American-raised Superman. He made some questionable decisions regarding dissension, but it was relatively tame and not too despotic. In fact, in the end he even let Lex Luthor think he had won and let him run the world. I doubt we’re going to see the same from The Utopian’s brother. I also found it a little hyperbolic that The Utopian’s brother compared 2013 to 1929 (on the previous page). I would have given Millar more leeway if this had come out in 2008. But, then again, that might be my political biases vs Mark Millar’s political biases, so I’m not sure. To see the other side of the argument, I do think it’s way too far on the other side for The Utopian to forbid his brother to help solve the World’s economic problems. I guess The Utopian probably sees it as a slippery slope where humanity becomes too dependent upon them and then makes it so that it’s much easier for a bad apple to steal control, but I’m not sure if I’m reading too far into it. Their argument probably would have been more fascinating in a medium that would allow a wall of text and more complex argument like a book rather than a comic book.

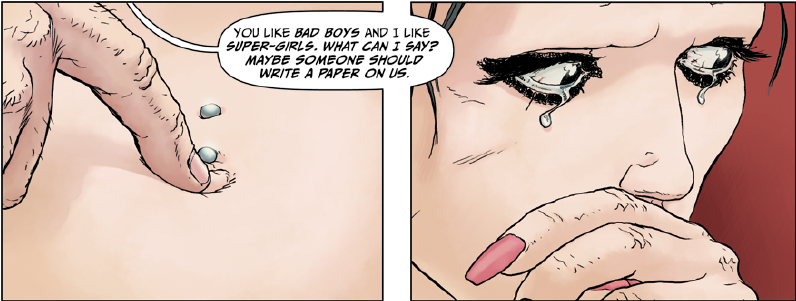

Before I move on to developments from the second issue I have to take a moment to address a club scene. I always try my best to read comics or experience any creative work without thinking too much about the author. Can they write a good book/screenplay/game/comic? Then I can enjoy it. As a critical reader (as I have to be for this site), I do consider a creator’s body of work for themes, influences, etc, but I try to keep their personal life out of things. However, Millar is quite controversial for the way he writes women in his comics. International House of Geek recently ran a piece about the rape scene in Kick Ass 2, for example. As a decent human being and a father to a daughter, I find these things to be questionable – although talking about things vs exploitation vs censorship vs female issues is a huge topic and not one I’d like to derail this post for. In general we at Comic POW! talk about these things when they occur in comics, but we realize it’s a complex topic. That is a large part of why I asked some women to write for the site – to make sure we are taking a look at how these issues affect people of both sexes. Nonetheless, while I am not reading Kick Ass because as of now I’ve considered it to be something I wouldn’t find entertaining – a little too over the top for me, I am ok reading Jupiter’s Legacy because it does not seem to have the same story-telling needs.

All of that was a pretty long-winded introduction to what I wanted to say about this club scene. Millar is drawing parallels with the fact that some socialites get treated like rock stars. The scene starts off quite well, actually. When the super kid is crude with the girl – suggesting that unless she’s going to give him sexual favors they can get out of his face – the girls call him out and leave. I found the scene worked really well. It revealed that this son of a super was a jerk and that even though he was super cool and popular, these girls had enough self-respect not to inflate his ego. But then it ends with what’s supposed to be the punchline – the girl who had so much self-respect has sent her friend to tell him that she’s waiting in the bathroom. I kept wishing and hoping that it was all a plot by a super villain to use his jerkiness and horniness to get him into a vulnerable position where he could be captured by the villain, but we never get any such resolution.

Now, I’m not naive. I know that some percentage of women (and men – although you don’t hear about those story as much) are willing to have sex with bands, actors, etc if it means they can be backstage with them. So I understand he’s depicting a realistic scenario, but it would have been so great if the punchline was on the super kid. Because I’m sure that for every woman (or man) who is told if they want to hang out with band member/socialite X that they need to perform some sex act, there is some percentage that tells them to eff off and leaves with their dignity intact. So with this incident I’m left torn because it’s nowhere near the same playing field as Hit Girl getting raped, but it still kinda sucks.

Additionally, although there are women super heroes mentioned, none of them gets the spotlight. A female super kid does get featured in the second issue, but it’s not exactly in the most positive light. It would have been nice if Millar could have done like Mark Waid in Irredeemable and had the women take a more active role. Then again, we’re only two issues in so maybe I’m letting my Millar biases creep up. Time will tell.

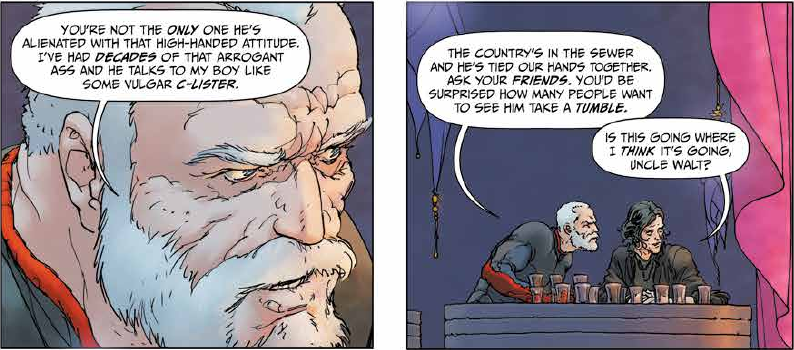

The second issue shifts focus slightly and brings in two more influences, although this time it’s two works from The Bard. Sure, William Shakespeare didn’t originate either of the two plots that seem to form the basis of this issue, but he certainly popularized him. Shakespeare reference number one comes from the focus of the issue: The Utopian’s daughter. She starts off with a typical socialite drug overdose that leads to a hospitalization. At the hospital she discovers that she’s pregnant and we soon learn that it’s with the kid of a Super Villain. Cue Romeo and Juliet! Given how apathetic the kids are about being super heroes I wonder if the kids of super villains are the same way. If that’s the case, then it’s possible that The Utopian would be less angry that it’s his rival’s kid that impregnated his daughter than the fact that she’s having a kid out of wedlock. Millar also borrows from Hamlet as The Utopians brother begins to resent his brother being the leader of the team – despite his brother’s visions leading them to the place where they got their powers. By the end of the issue he’s conspiring to kill his brother. However, unlike Hamlet, it appears that The Utopian’s son will be in on the plot.

So Millar gives us a lot to chew on. He’s borrowing from a lot of places, intentional or not. He’s holding up a mirror to America in an attempt to inform as he entertains – perhaps even bring the Depression to the forefront for the first time for some of his readers. We have generational conflict as well as mutiny. Millar has certainly created a compelling world and one in which I wish to do some more exploration.

Jupiter’s Legacy: Written by Mark Millar with art by Frank Quitely

Millar’s mode is adolescent male power fantasies, so it’s not at all surprising how that super kid acts and how he gets rewarded for it. I mean, sure, most comic books are adolescent male power fantasies, but Millar’s stuff is even more sophomoric than that…ugh…Millar…

[…] super hero union that works together with the city of Chicago to contract super hero services. Like Jupiter’s Legacy it combines elements of Top 10 (suddenly there are super heroes around the time of World War II) […]

[…] Twelve gods will be briefly reincarnated in order to perform miracles like superheroes and bask in celebrity fame. But for the first time, there may be a thirteenth god reincarnated, and lucky number thirteen is tipping the delicate balance. Interestingly, it’s also a direct rejection of Jupiter’s Legacy. […]