note on all the image scans: they are correct manga-style so they are read right to left

Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. I think it works well as it is the only manga I have which is set in Japan and does not have fantastical elements. It’s not that Ranma ½ can’t teach us about Japanese culture (in fact, I’d like to explore it in a future post – especially comparing the fact that Ranma is written by a woman and Love Hina by a man), but it’s going to be skewed by the fantastical gender-bending (and species-bending) aspects.

Love Hina is often put into the Harem Manga category. Harem Manga involve a central character, often a male, being pursued by many females. The center of the harem may or may not return the affections with one or more of the harem members. This can be played for laughs when, as in Ranma ½, the main character doesn’t want ANY of the girls. Or it can be more dramatic if the main character only wants one of the girls. It’s been a decade since I read Love Hina and I didn’t even finish it back then. I didn’t get the last two books until a few years after the first twelve and so I knew I’d have to reread them in order to appreciate it. That’s why I found it such a great proposition to use Love Hina as my first foray into covering manga at Comic POW! That little tangent serves as my caveat for the following assertion (given I may be wrong, but I don’t remember): I don’t think Love Hina truly belongs in the harem category. Sure, superficially we have one guy living in a house with a bunch of girls (we’ll get to how this happens in due time) and eventually there’s even a love triangle of sorts. But the girls aren’t all after him. In fact, for a good chunk of the story, most of the girls are indifferent to him and some are actively hostile towards him.

I do recognize the limitations of putting too much stock into Love Hina as a window into Japan. First of all, it’s a comedy; imagine trying to figure out American teen culture based on Superbad. There are kernels of truth there, but comedy is built on exaggeration. Additionally, the story is a love story and those also suffer from various suspensions of disbelief in order to make them work. That said, I think there’s a lot of interesting stuff in here.

So the format will be one book (as collected by TokyoPop) per entry. I’ll cover the general plot of the book and then dive into various interesting things about the book. I’m not sure at this stage whether I’ll always be exploring topics that could have headers (eg “Sex”, “Gender”, “University Life”) or whether I’ll just go in paragraph form. We’ll see what evolves as I write this as well as over the first few entries. When I finish covering all the books I intend to view the anime series (another thing I never finished – didn’t want to ruin the book ending) and do a comparison between the two.

The Story

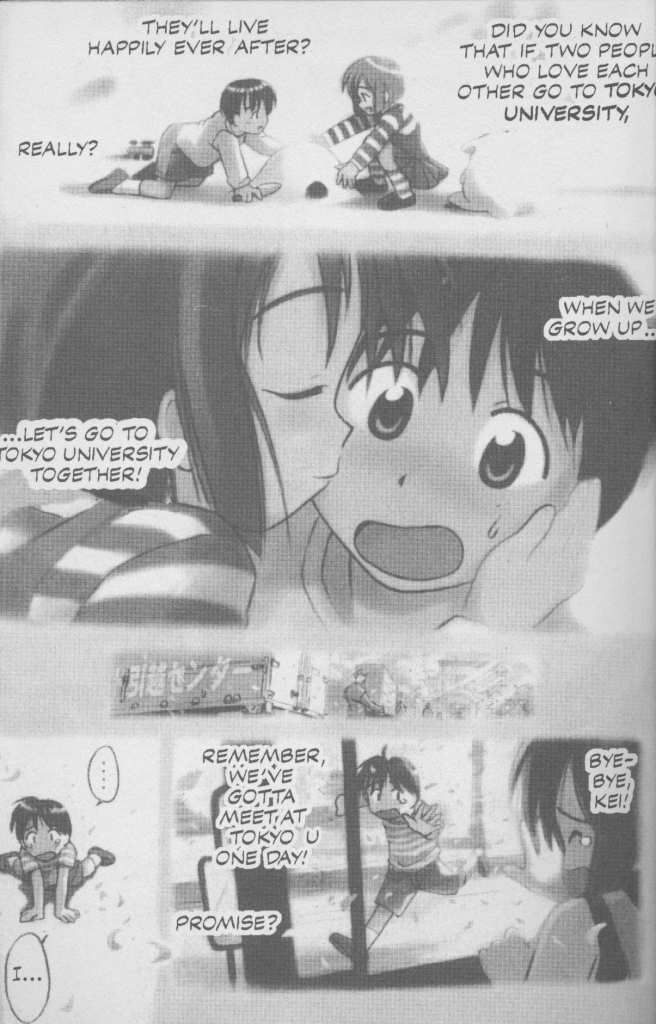

Love Hina starts off with us seeing the flashback that has lead out loser-protagonist to try to get into Tokyo University. The book makes it out to be like getting into an Ivy League only with even more prestige than that carries in the US. (We’ll get to what that means soon enough) Keitaro wants to go to Tokyo University because he promised a girl he’d go there when he was around 4 years old. His parents kick him out for having failed the exams twice, but still trying to get into Tokyo University instead of trying for an easier school or just getting a job. So he heads out to the hotel his grandmother runs, Hinata House. He is doing this on a lark because he hasn’t spoken to her in ages or he’d know that it’s no longer a Hotel. He lets himself in, which seems weird to me. Do the Japanese not lock their doors? (After all, it’s no longer functioning as a hotel) Perhaps it’s just unlocked due to the Rule of Funny. Eventually he decides to go to the hot springs bath (this appears to be a hot springs vacation destination town). In what appears to be the template for these types of manga (Ranma ½ also does it), Keitaro and Naru see each other naked. And, although it was due to a misunderstanding, Keitaro is branded a pervert. (Again, parallels to Ranma ½)

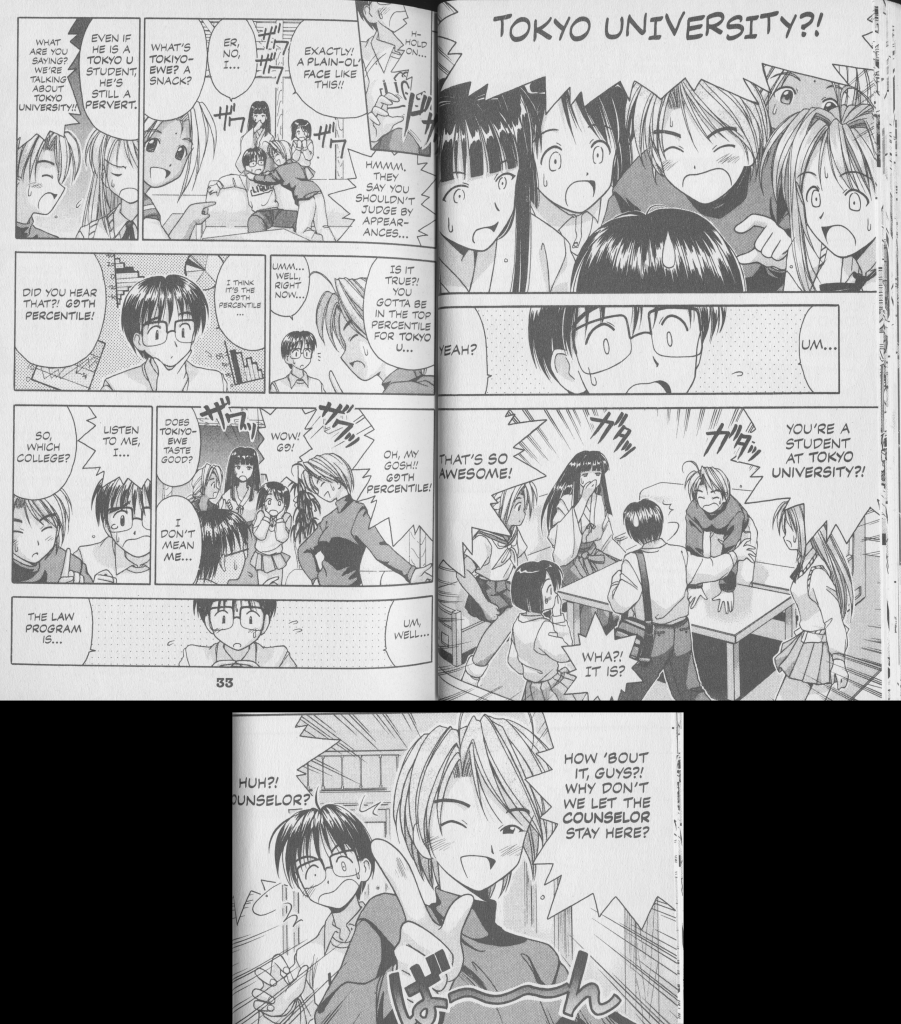

Eventually, he runs into all the girls living at the hotel and is about to be reported to the police when his aunt, who’s been looking after the place while grandma is gone, shows up and rescues him from that fate. Through classic comedy misunderstandings the girls end up thinking he goes to Tokyo University for Law and decide he can live there as their landlord. In any other story, this would be the main conflict. How will Keitaro keep this a secret for surely they would kick him out if they found out. Akamatsu turns that on its head by having Naru discover this fact almost immediately. The girls DO kick him out, but then Keitaro is saved by deus ex abuela – his grandmother had put him in charge of the hotel. We kind of have to handwave this because as far as we know, he hasn’t contacted her to let her know he NEEDS to stay there and his aunt seems to be doing a good enough job maintaining the place. But, hey, Rule of Funny. The girls decide they can’t disobey grandma and force him to leave (another discussion point) so they try to make life unbearable for him.

We see him go to his Cram School (prep school for the college entrance exams) and find out that Naru goes to the same school. We find out she’s in the top 1% on the test scores and she ends up tutoring Keitaro. From that we learn that his failure to pass is somewhere between him having a lack of confidence and being a poor student – and perhaps a little dumb. Which is not quite the narrative setup I expected. After all, the former can be overcome, the latter maybe not. So you can see why I enjoy Ken Akamatsu’s writing – lots of subversions and aversions of comedy tropes.

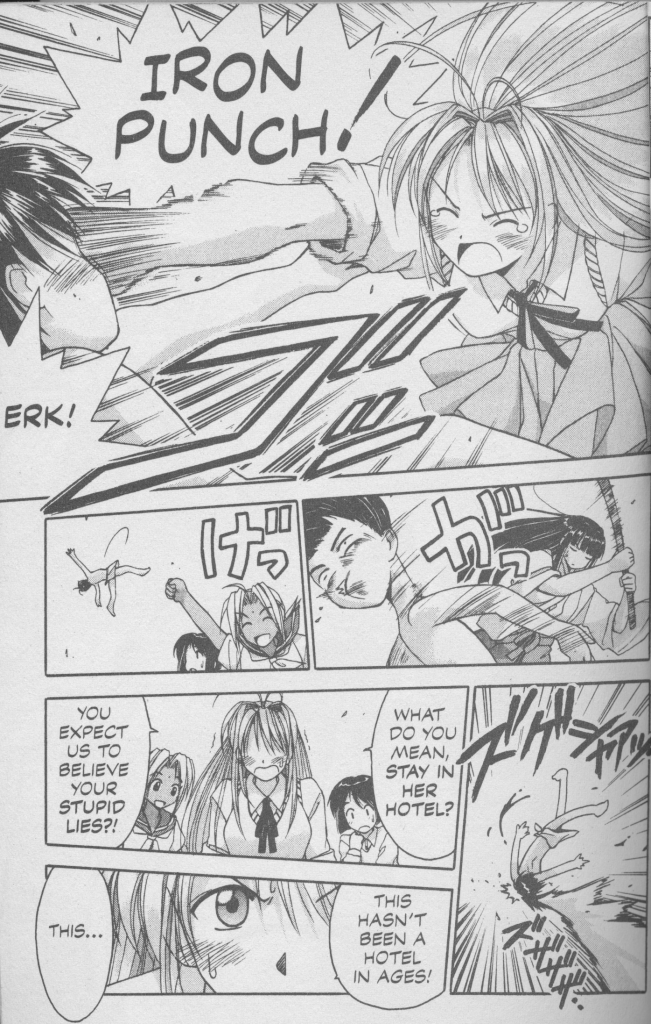

Scattered throughout all of this are a series of events that are part clumsiness and part dumb luck that keep getting into Keitaro’s way in his insistence that he’s not a pervert. In what is somewhat the luckiest of bad luck he seems to always end up landing head-first into someone’s breast or falling through a floor into a room of naked girls and so on. It’d be awesome for him if the consequences weren’t so bad. Although, I do like Akamatsu’s reality-based writing in that even though Keitaro is being physically assaulted for clumsiness (and, therefore, things that are not his fault), Keitaro does still daydream (and other things we’ll get to later) of the naked chicks he’s seen. In other words, he’s virtuous enough not to take this situation to a scary place, but he’s still a 19 year old virgin for whom seeing all these naked chicks is a dream come true. And then there are the great comedic scenes such as when Naru has Keitaro duck under a table to hide the fact that he’s in her room. Of course, this being Japan, they’re sitting on the floor so as the other person decides to sit on the table, he’s essentially forced right up into her crotch to keep from being detected. This, for a guy who has never even kissed a girl and it’s under the prompting of the same girl who keeps calling him a pervert.

Finally, the book ends with Motoko, the warrior-girl, thinking she’s in love with him and it turns out she just has a cold. This is the one place, so far, where the book leaves reality far behind in favor of making Motoko a martial arts parody. She can cut falling leaves with her sword. The force of her blows can split rocks, etc. I remember the episode of the anime that coincides with this story and they even took it further by making the animation style look like those old martial arts movies.

OK, time for the analysis. I think I’ll go with header-ed sections for this entry and we’ll see how I feel about it when the next one comes around.

Life in Japan

Japan is a country in transition. I don’t know what the root cause is, but everything I’ve read recently seems to suggest that Japan is transitioning away from the stereotypical Japan focused on honor and The Group and towards a more Americanized culture. The transition isn’t as clear-cut as that; almost no cultural change ever is. Instead of a mix between a step-by-step evolution and a hodgepodge of traditional Japanese and American. A lot of times, the way things change is through humor and satire. If you say some part of culture doesn’t make sense, you’re attacked for upsetting traditional values. But if you use humor to point out its absurdity, sometimes that can help people see how crazy things are. I think Keitaro’s childhood promise has many purposes in this story. It is a romantic notion – that two kids would make a pact to meet up in the same university 15 years later. It also gives Keitaro a powerful incentive not to quit even after failing two times in a row and not having any real chance of getting in. But I also think that Ken Akamatsu is also making a commentary on the silliness of pacts. Stereotypically, the Japanese take these very seriously. There are all kinds of pacts including suicide pacts if two kids are kept from being in love by their parents. Akamatsu turns it on its head by making it absurd on at least two levels. One, how could two little kids know they’d have the chops to get into Tokyo University. I forgot if the thought ever comes to Keitaro’s mind, but how does he know that the girl he’s supposed to meet there is smart enough to get in? And why does he have so much faith in a childhood pact? That would require stereotypical levels of commitment on the girl’s part. He IS smart enough to bring THAT up with Naru and Akamatsu uses it to foreshadow the fact that Naru is doing something similar. (Although it isn’t made clear in this book – I just happen to remember that from the previous read) But, second, it’s absurd because Keitaro neither remembers the girl’s name or face. So even if they do make it to Tokyo University (after all this pain he’s put himself through), how can he be sure he’ll find her?

It’s interesting that Keitaro mentions that he is considered a 2-year ronin. During Japan’s feudal period (which ended around the time of the American Civil War), a ronin was a samurai without a master. It was meant to be a title of shame because the ruling class did not want samurai to have the idea they should be without masters. It took on an even more shameful tone in the later half of the feudal period when there was greater samurai unemployment so some of them used their awesome skills as mercenaries and for other undesirable trades. I’m not sure, but the Japanese seem to look upon the samurai with as much romanticism as we do with the Wild West. (And their films – as far as I know – also tend to be as inaccurate as our Wild West films) So it is definitely an interesting cultural shift that a student who failed to get into university would dare compare himself with the likes of samurai, by taking on the name ronin. And the book does seem to have Keitaro and his loser friends view it as both a shameful and a prideful term – in an almost punk sense of the word prideful. No doubt, Akamatsu would have been channeling kids who’d seen samurai movies romanticizing the ronin notion and would take some perverse pride in the title.

As I mentioned above, Keitaro has been kicked out of his house for failing twice and still attempting to get into Tokyo University. I imagine having such a layabout son would be a sense of shame for any culture, but I was somewhat surprised by this development. On the one hand, given how stereotypically small many Japanese houses seem to be, I could see the parents wanting to kick him out. On the other hand, I would have thought such a family-oriented culture would allow him to stay. Or maybe it’s just Akamatsu coming up with a reason for him to have to live at the Hinata Hotel.

Based mostly on having watched/read a lot of anime/manga that takes place in high school and college, it appears that the Japanese really take their hobbies seriously. We have clubs in our high schools in America, but nothing like the organization displayed around the clubs in Japanese media. Keitaro’s hobby is scrapbooking – specifically taking photobooth photos. This seems to be in line with other media I’ve seen/read as a pretty popular thing among high school kids in Japan – orders of magnitude moreso than in America where I’ve probably seen two photobooths in my entire life. Akamatsu uses this as another way of marking Keitaro a loser by having him take photos of himself. That would pretty much make him a loser in America, as well.

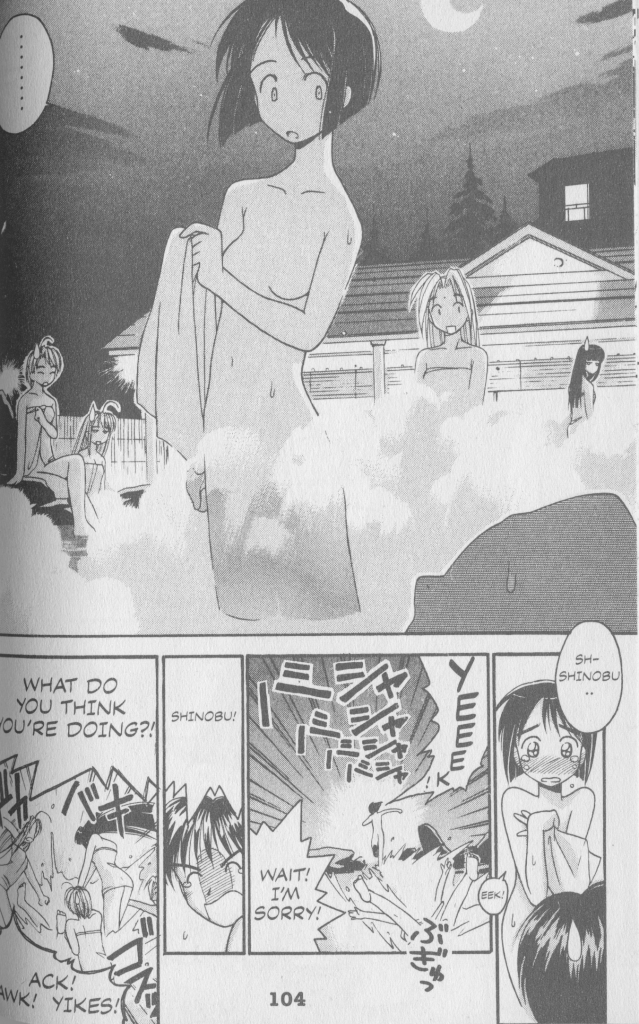

The Hinata Hotel has a hot springs and Keitaro mentions early on its in a hot springs town. Many manga and anime that involve sexual tension usually involve a trip to the bath house. I remember reading about these in a book I bought when I was planning a trip to Japan (that sadly never happened). I think it’s interesting in that we had these in Western culture during the Roman times. I recently read a book that suggested the setup was pretty similar to what we see in most Japanese media – there’s a pre-bath where you get most of the dirt off your body and the soak is really almost more of the way we treat hot tubs/jacuzzis in the West. The main difference is that the Japanese baths are used in the nude. Of course, just like a steam room in the West, you’re supposed to cover up your genitals when you’re walking around, but everyone’s pretty much chilling naked in this giant jacuzzi. (Or hot springs) Since the story takes place in what was once a hotel, the implication is that the people there would be strangers. I wonder (and some of my readers have been to Japan, although I don’t think they went to a bath house) what the etiquette is on conversation. The Hinata girls are chatting it up and other things (we’ll get to in a bit), but they’re all friends. I know (both from common sense and the book I read) that etiquette dictates not staring at each other’s naughty bits if you’re in a coed bath, but other than that, I’m not sure.

We now arrive at what I think is perhaps one of the biggest puzzles for me with Love Hina where I’m left wondering if this is a cultural learning opportunity or whether this only exists for the purposes of story and comedy. Why do all these girls live at Hinata Hotel? Here is the list of girls:

- Naru Narusegawa (17 years old) – High School Senior

- Mitsune “Kitsune” Konno (19 yo) – Freelance Writer

- Kaolla Su (13 yo) – Eighth Grade

- Shinobu Maehara (13 yo) – Seventh Grade

- Motoko Aoyama (15 yo) – High School Sophomore

Under what circumstances would all these girls be living together in the same place? The only person who clearly would have to stay at such a boarding house would be Kaolla Su because she’s a foreign exchange student. Everyone else should be with their parents. It’s mentioned that Shinobu has trouble at home (I think it’s divorce in the anime) and that Motoko’s parents live in the hills or some kind of training monastery. But would parents really allow all these underage kids to be living away in a former hotel? In real life Mitsune might be bringing boyfriends back to her room. And, Keitaro, as I mentioned before, just walks in and goes to the hot springs bath where he proceeds to see Naru naked. Again, it’s a comedy, but things could have turned pretty dark in real life. I would imagine that Kaolla would really be living with a family and/or Motoko would be in a boarding school. So, as I said in the first sentence, is this something that could really happen? Or is it just for the laughs? (Part of the problem of using a comedy as a cultural learning tool, perhaps)

Plausibility of the living situation aside, I think it’s very interesting that Akamatsu has Kaolla Su around as a character. Kaolla is from not-India (it’s a huge source of jokes that pretty much everything about her in both the anime and manga seems to point to the fact that she’s Indian, but officially no one in-universe knows where she’s from) and that’s special because Japan is a pretty closed place to foreigners. I’ve read about it in books like Tokyo Vice and my brothers have experienced it live. People in Japan are polite, but extremely unwelcoming of non-Japanese becoming permanent residents. Then again, as you’ll see in later books, Akamatsu has a pretty forward-thinking group as the cast expands a bit more later. Perhaps he’s using it for the dual purpose of the humor in the other (which Kaolla provides tons of) and of trying to show other Japanese that perhaps they should be a bit more tolerant of others.

I mentioned above that we’d talk about how going to Tokyo University seemed to be even more impressive than going to an Ivy League. The image above is why. In the preceding pages they were ready to kick him out because of the rational reason that this is a girls’ dorm and he’s a guy. It makes sense under any culture that you would not want a 19 year old landlord to reside over a dorm with girls from 12-19 years old. It’s not about what any one guy would do, it’s about what any guy MIGHT do. I certainly wouldn’t feel comfortable with my daughter there. Interestingly, maybe I’m forgetting a scene, but I don’t think the girls’ parents ever find out about this development. Anyway, they’re ready to kick him out when they “find out” he’s a Tokyo University student. And, according to comedy convention, this lie gets compounded into him being a law student. Suddenly, they’re all – well, a Tokyo University student would never do anything bad to us. As though intelligence and creepiness were inversely related. We fall for that to SOME degree in America, but not enough to let a guy run a dorm full of girls. Still, it seems as though there mere fact of being a student there (not even a graduate) carries a great deal of weight in Japan towards vouching for moral character. If that’s true, and Akamatsu isn’t exaggerating too much, it would definitely make sense why the university would have such pull. In America, going to a good school gives you bragging rights; it appears to give so much more in Japan. In fact, Kitsune is willing to allow Keitaro to grab her breast and later pronounces it’s OK for him to be a bit pervy. (Of course, part of this is her scheme to get married to him and get all his law job money. “money-grubber, like a typical kansai (western Japanese person)” – Kitsune’s description at back of book)

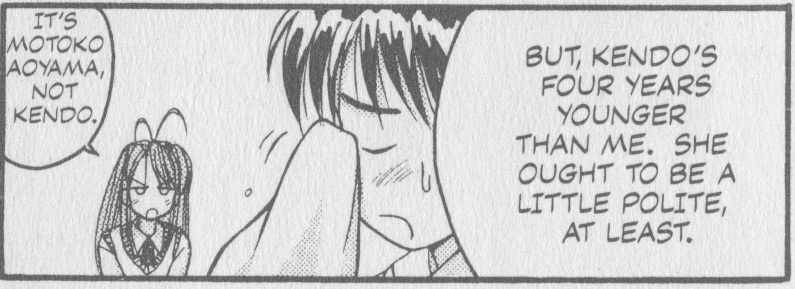

Returning to the conversation about stereotypical Japanese culture, another thing every American knows is that Asians in general are very respectful to their elders. This is another one of those stereotypes, like the seriousness of the pact, that I imagine is adhered to various degrees in Japanese culture. For example, Keitaro is annoyed that Motoko is not showing him the respect he feels he deserves as someone four years her senior.

But the girls, as a whole seem to respect their elders because they don’t want Keitaro to be their landlord, but they decide they’ll need to try and force him out so they don’t disobey Grandma’s orders to let him run the place. (Weird thought process there, grams) So it would seem that society is moving away from this in the sense that there’s less respect for people a few years older than there used to be. This jives with my real life experience with Asians, including my in-laws. The previous generation uses honorifics (older brother, aunt, uncle) with their siblings while my wife’s generation doesn’t. (Although it’s a bit uneven – some of her cousins do)

As happens in various media where there are a variety of women (especially in broad genres like comedy), it appears that the girls at Hinata House are all manifestations of different aspects of the female. (For a western example, think of The Spice Girls – the rich one, the sexy one, the kiddie one, etc) Shinobu is the traditional, domestic woman. She’s awesome at cooking and humble. Kitsune represents the sly woman and the woman willing to blackmail you with offers of her body. She seems willing to use sexual favors to get ahead. She’s also the party girl – always drunk – which causes some problems in book 2. She’s a freelance writer which means she doesn’t have to be an office girl. Motoko is the noble warrior. She represents the romanticism of Japan with its martial arts past and honor. Naru is the woman that Japanese men are intimidated by. She can cook OK, but the presentation sucks – and she doesn’t really care. She is violent and doesn’t take guff from guys. She’s the woman that’s causing some men in Japan to just have pillow girlfriends. Kaolla is more about her foreignness than womanhood, but she’s an agent of chaos. In Western culture she almost fits into the manic pixie dream girl role.

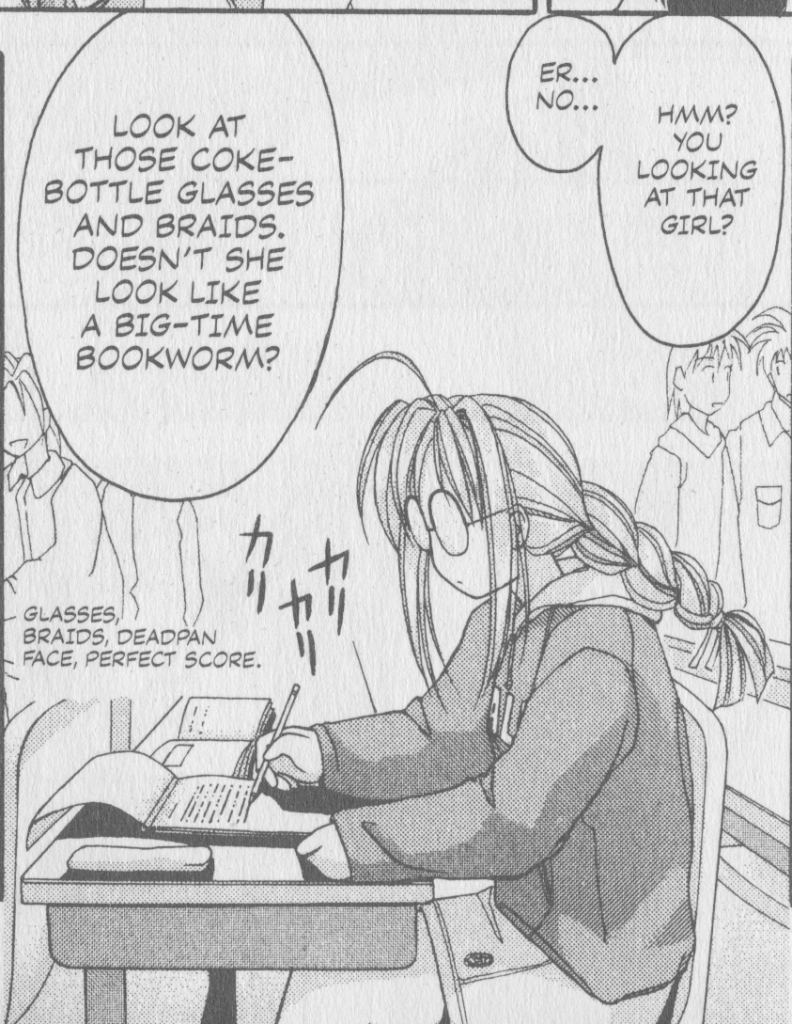

In the West we stereotype the Japanese (and Asians in general) as studious types. But this is clearly an exaggeration because Love Hina has the characters point out how nerdy Naru is. And, interestingly enough, she seems to be a nerdy girl who cleans up nicely. That is to say, when she’s in nerdy mode she doesn’t look cute. The anime goes even further in exaggerating how bad she looks when she’s dressed nerdy. Both the anime and the manga have her look SO different that Keitaro doesn’t even recognize her. (Although I’m pretty sure in the anime he meets her as a nerd first while in the manga he already knows Naru quite well before he sees her nerd personality) Anyway, I would have thought this was a Western construct. And it’s possible that it is and that it’s been transplanted to Japan from the West, but I do know that glasses are a sign of nerdiness/ugliness in many manga/anime I’ve read/seen.

Near the end of the book, Motoko thinks she’s in love with Keitaro. I think it’s interesting that she essentially names all the same types of things an American high school girl would. I would partially expect that because it’s the same brain chemicals and all that around the world. At the same time, different cultures do have different ideas about falling in love, so I wonder if some of this is due to cultural transfer.

I just wanted to take a quick moment here in this section to say that the Japanese are obsessed with blood types in a way that we aren’t in America. I first noticed this with fighting games that had originated in Japan. In Love Hina Aunt Haruka gives Keitaro a fact sheet on the girls. It contains their age, birthday, grade in school, height, weight, bust size, and blood type. I know everything after grade in school is fan service for the reader, because Keitaro isn’t about to go buy bras for the girls or something, but I just don’t understand the blood type obsession.

Finally, at the end of the book there’s a sketchbook section where Akamatsu talks about his original designs for the characters and how they changed as he plotted the book. And he mentions that Kaolla Su spoke a certain dialect of Japanese because of which of the girls she was closest to. And it made me sad that I don’t speak Japanese because that’s something we just lose in the translation. It’s usually approximated in anime by using Southern or New York accents, but really this is slightly more than accents. It’s certain words, phrases, and metaphors that just don’t translate over. After all, just because of where Kitsune’s from you’re supposed to know that she’d be money-grubbing. Additionally, you might notice in these scans that there are seemingly random untranslated Japanese words all over the place. I’m not sure if it’s always been this way or if it’s from the post-World War II manga culture, but the Japanese are obsessed with onomatopoeia to the point where they have it for sounds and situations we don’t normally associate with that. It’s a shame I can’t read, say, the sound of a Japanese style door opening. Or the sound of someone fainting from seeing something sexual. It’s part of why I advocate learning more than just one language.

Gender/Sex Norms

An interesting thing I noticed in comedic manga/anime from the beginning is that there tends to be a lot more comedy around touching and groping of breasts. This happens whether it’s a story written by a man or a woman. In the West we have comedy that revolves around breasts. The first thing that came to my mind was an early scene in Broken Lizard’s Beerfest where the entire humor of the scene comes from a chain reaction that results in nearly every woman at Oktoberfest having her blouse ripped open, revealing breasts. But I’ve never seen physical comedy revolving around breasts in American cinema or comics. But clumsy Japanese dudes are always falling into breasts or falling and ending up with their hands on a breast. As we’ll discuss later, there’s a lot of breast squeezing. (Which I’ve seen here, Ranma ½, and Azumanga Daioh among other places) It’s a very interesting place where our ideas of what’s funny diverge. What I’d like to know is the reason for it. As I mentioned, it’s not as though we can lay the blame at the feet of male writers. Is it because of male readers? It is my understanding that manga reading is much more co-ed than comics are in the US. Perhaps it is linked to body shame? I’ve read from trustworthy sources that the Japanese are more sensitive about some body things than we are. An example is that Japanese women don’t like others in the bathroom to hear them pee, so they flush as they’re peeing. In America we tend to be sensitive about poop sounds, but I don’t think the majority of people of any sex care about the sound of pee. Additionally, there’s the somewhat larger tendency towards public groping in crowded places (I’ve heard first hand in addition to seeing it in manga/anime). So maybe it’s coming from the universal impulse of finding humor in what we are most nervous about.

While I’m on the subject of breasts, the precipitating event for Keitaro being named a pervert stems from when Naru first comes into the bath. She, like many other manga/anime characters with glasses, tends to end up in Mr Magoo-like situations because she’s essentially blind without them. She thinks Keitaro is Kitsune and mentions that her breasts are getting bigger. She invites Keitaro to feel how they’re getting bigger. Also, later on, Kitsune and Kaolla find out about this and give her an uninvited grope.

I must admit that as a guy this is one area where I’m least prepared to say whether this is universal or if it tells us something about Japan. On the one hand, I know that Asian women are on the smaller end of the breast size scale on average. In Azumanga Daioh the girls make a big deal out of the one girl with the larger breasts, to her consternation. And in my wife’s family, those with larger breasts get some light teasing. But what of this asking friends to squeeze breasts? I DO know that this happens in America when women get breast implants. When I was a lifeguard, one of the female lifeguards got implants and she invited all the other girls to feel how real they felt. But, not being a girl, I don’t know what girls do here – I imagine it’s probably highly individual. After all, that’s how it is with the whole practicing kissing with each other. I knew some girls who did that and others who found the idea gross.

Going to another topic entirely, Keitaro is essentially everything a male is not supposed to be. The only thing male about him is his obsession with the female body. He’s clumsy, he’s not too smart, he lacks ambition (other than to meet that girl at Tokyo U, which he only does because it’s his only chance at a girl), he’s so weak that even the youngest girls can beat him up. It’s definitely an interesting gender study in that the girls are all exemplars of various female gender stereotypes while Keitaro seems to lack them all but horniness.

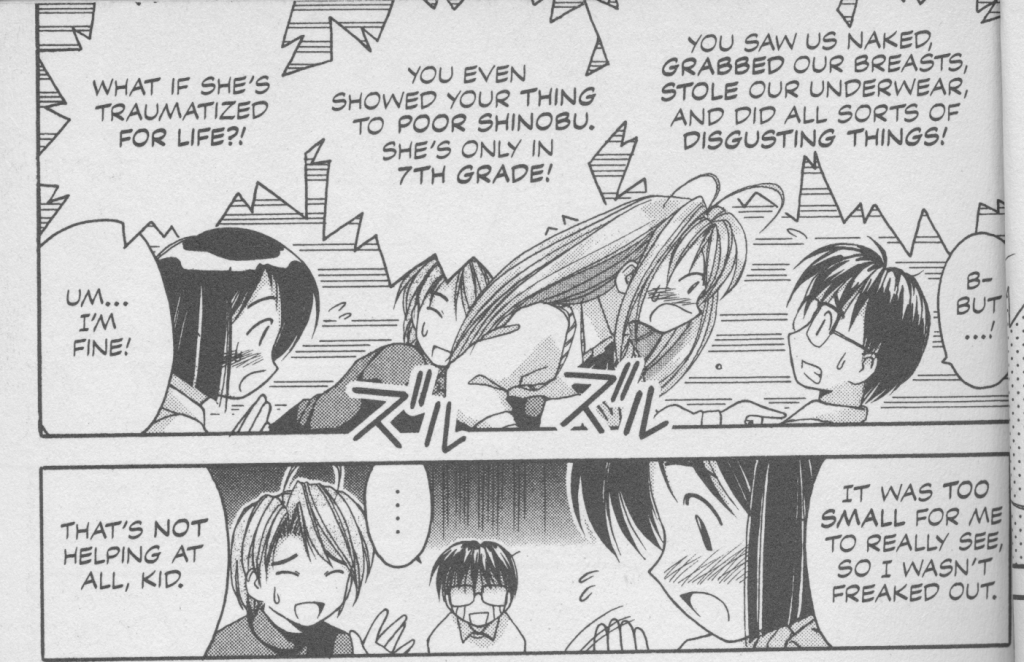

Americans (or at least the ones who determine what makes it into comics and onto our movie screens) are so afraid of potentially latent gay feelings that we are just starting now, after over 100 years of cinema, to find humor in penises. It’s why it was such a big deal for Jason Seigel to be naked in Forgetting Sarah Marshall. Even in our rated R movies, full frontal male nudity is almost non-existent. But just by watching rated R movies like Kramer vs Kramer (which my parents let us see), I’d seen vaginas way before I was actively seeking them out. But it’s quite a trope in Japanese media to make fun of small penises. (Parodied in the Chinpokomon episode of South Park – and Stone and Parker are into Japanese culture so they probably grabbed it from there) The image from above is the aftermath of Keitaro accidentally flashing young Shinobu when he was running around in a towel. So I’d say that here the humor is probably universal, but the Japanese are just way ahead of us on exploiting it. And, of course, everyone knows that the humor is born of insecurity. While women (some women) compete on breast size, men are “lucky” in that their equivalent competition is hidden. (At least in modern times. Back when men wore tights, they combated this with the male equivalent of bra stuffing – the codpiece)

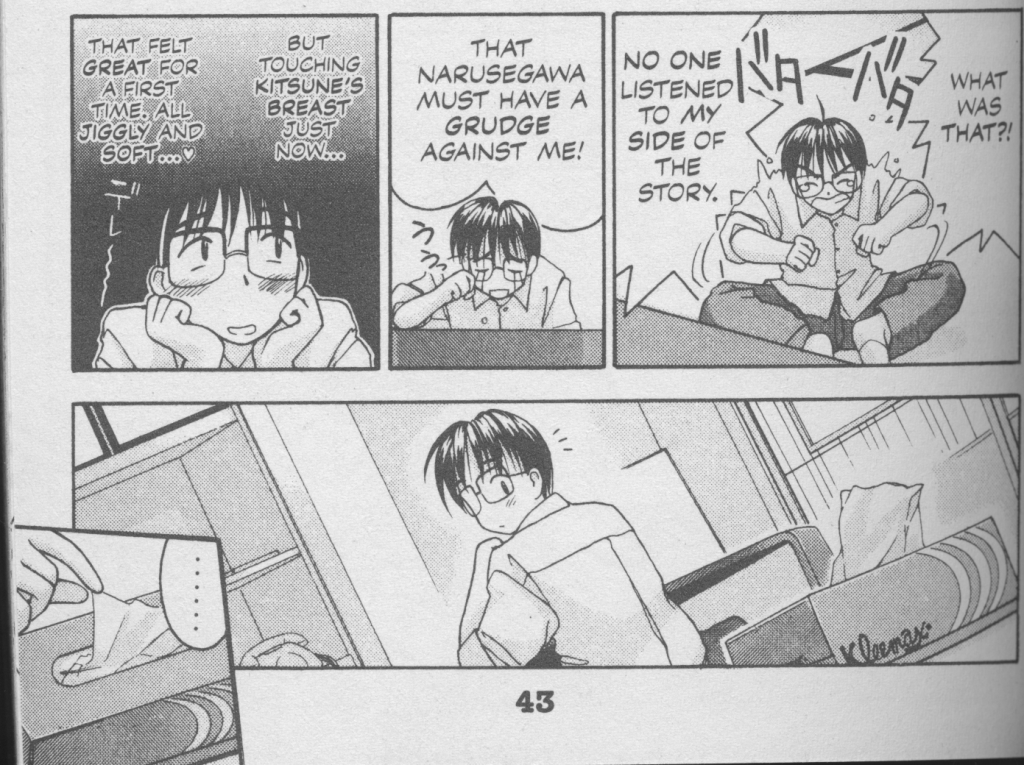

I once watched a documentary about how in America you can see someone getting destroyed by violence and just get a rated R while just showing the pubic hair area on a woman was really tempting the ratings board to give the movie an NC-17. We truly are way more afraid of our sex drives than our violent urges. (THANKS PURITANS!) And while a few mainstream (ie not-porn) movies have contained scenes of male masturbation (female is next to unheard of) like American Pie, I’ve yet to see any hint of it in mainstream comics. Oh, you can see Batman villains beat someone to a bloody pulp or brains splattered everywhere in a more violent comic. But you’ll never see someone jerking off. Interestingly, from what I remember of the anime, these scenes were removed – showing that, perhaps, even Japan has a different standard for manga than anime. Still, I think it’s remarkably honest for a dude who is not getting ANY and is surrounded by women and is constantly, accidentally seeing them nude.

Speaking of things you’ll never see in American comics. I’m reading the Tokyopop translation of Love Hina. It’s rated “Teen 13+”. So I’m not sure if they cleaned up the above image and some of the other hot springs images. In the scene above, Keitaro has just falling from a tree he was in after falling off a ledge. He looks up and sees the 12 year old Shinobu naked. That’s right, 19 year old Keitaru sees Shinobu naked. This is actually a huge plot point for quite a few pages as it builds up with other things he accidentally does – like end up with her panties when he crashes into her after she’s finished doing the laundry. I’m pretty sure if this image WAS NOT censored, it couldn’t be sold in America under the latest revision to child porn laws. And, interestingly, later Keitaro is shown to be blushing over having seen her naked. However, before you get too judgmental on the Japanese, I’d point you to the episode of Seinfeld where Jerry and George nearly lose their chance to make the show-within-the-show pilot for Jerry because George is caught looking at the executive’s daughter’s cleavage after being nudged by Jerry. The girl is 15. When Elaine is disgusted, the conversation goes like this:

ELAINE: Look, I don’t like people talking about my shoes behind my back, okay? My shoes are my business. The two of you shouldn’t have been looking at some fifteen year-old’s cleavage anyway!

GEORGE: He poked me!

JERRY: There was cleavage in the area. That’s a reflex – <mimics nudging someone with an elbow> – cleavage-poke, cleavage-poke…

ELAINE: But she was fifteen.

JERRY: You don’t consider age in the face of cleavage. This occurs on a molecular level, you can’t control it! We’re like some kind of weird fish where the eyes operate independently of the head.

Now, you might say there’s a world of difference between 12 and 15. I’d say yes, but not in the eyes of the law. So, while Akamatsu seems willing to take things way further than we generally would be comfortable in America, it’s not unheard of here to use under-aged gawking for humor’s sake.

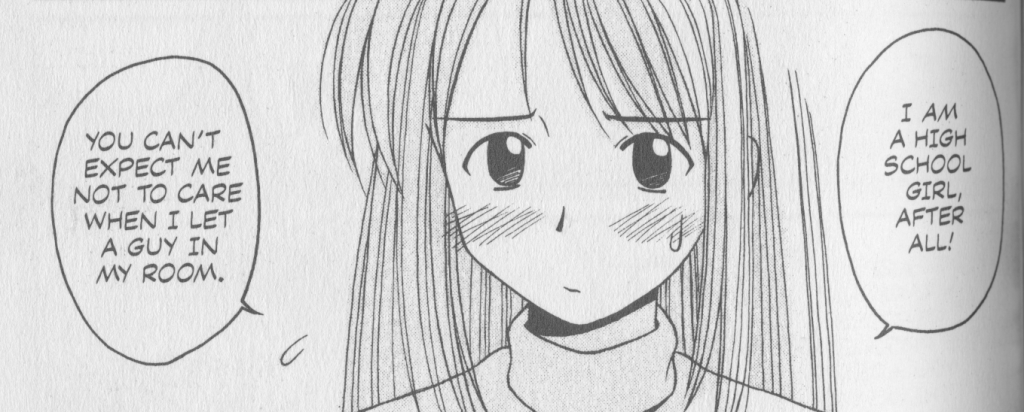

Finally, as written by Ken Akamatsu, the feeling of letting someone of the opposite sex into your room seems to be universal.

So, there we go. That’s part 1. I don’t expect every part to be as long as this one since there was a lot of setup exposition, but time will tell. See you next time!

Points you brought up that I know a thing or two about:

Ronin

It’s an acceptable term for a kid who failed his entrance exams (it’s also used for salarymen between jobs) because, like a samurai without a daimyo, they are without a master, be it a university or employer.

Boarding Houses

Maybe I watch too much anime and play too many video games, but it seems to be not atypical (although probably not in the majority) for a family to send their kids to another area and put them up in a boarding house to attend a specific high school. That’s what Hinata House is now, not a hotel.

University of Tokyo (Todai)

That’s the Harvard of Japan. It’s seriously the most prestigious and awesome school in all of Asia (#1 in Asia, #20 in the world). It’s kind of implied that Akamatsu is making reference to Todai no matter what he calls it in the manga. Big deal school for sure and its students are a big deal as they’re probably set for life.

Blood Types

I think you kind of hit the hammer on the nail here. The same way people would predict personality types with astrological signs in the states, blood types can be used as a shorthand for personality types.

Onomatopoeia

Japanese is just really focused on onomatopoeia in the way they write. They’re really tightly bound and useful as a shorthand.

When I was doing my research I saw that ronin is the right term, I just think it’s such an interesting change from what it originally meant. Both in that now all classes of society can use it and also that it was originally a shameful thing. Now some wear it as an ironic badge of pride.

Ah, thanks for the info on boarding houses.

Again, as for Tokyo U, I know it’s like Harvard, but I see it as so much more.

Blood type – neat info.

I don’t think ronin is meant to come off as a badge of pride at all. Keitaro and his buddies make it seem cool because they’re all losers. I think you’re supposed to interpret him as a loser to start off the manga.

Haha, good point, good point. They are pretty loser-like.

By the way, did you notice the Azumanga Daioh references? That anime was way better than I thought it’d be. It would definitely make for some interesting articles.

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Understanding Japanese Culture, Humor, and… […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] I’ve never read one. Even the lifestyle manga I’ve been featuring here on Comic POW!, Love Hina, posits violence as the response for Keitaro’s sexual infractions, even when they’re […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

[…] Spend enough time doing critical readings of media and you come across the assertion that all media tells you about the culture it was written in. Sometimes, as in contemporary media, this is easy to tease out. Other times, as with science fiction, it’s by extrapolation. So I thought it might be interesting to re-read Love Hina, by Ken Akamatsu, as a way to to understand Japanese culture. Part One can be found here. […]

Reading this in 2016. Really interesting stuff. I’m going to be reading it as i rewatch the anime.

Awesome. It’s been my intention to continue the series with the anime, but I’ve not had much time recently.

I’m excited that someone else is as interested love hina as I am. It was one of the first manga I ever read all the way through and I just couldn’t get enough of the unique humor and situations to manga that you don’t find in western stories.

Great! Well, I hope you enjoy the series. I enjoy conversing with readers, so feel free to comment on any of the articles and start a conversation.